February 15th, 2013 — Clarion-West-2008, Seattle, Space

This post is the eighth in a series of ten about my experiences at Clarion West Writers Workshop (Wikipedia; Twitter) as a member of the 2008 class. I’ll talk about the final week of the workshop, Week 6, when Chuck Palahniuk (Wikipedia; Twitter) instructed. (It’s pronounced PAUL-uh-nick.) Here are Parts 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, and 7 of the series. In Part 7 I talked about Sheree R. Thomas‘s week and the beach reunion my class held in October 2011 in San Diego. We’re tentatively discussing another reunion now — maybe Las Vegas or Portland.

I should note that on August 31 2009, my Clarion West comrade Pamela Rentz said as a comment to Part 3:

Cool! At this rate you’ll have the workshop covered by 2012.

It is now February 2013. Part 7 was published on January 3, 2012 — more than a year ago. At this rate I hope to have the workshop covered by the time I’m dead.

Of course, Week 6 was the last week, so this should be it, right? Except for the remaining Parts 9 and 10. I think Part 9 will be my last remarks on the ’08 workshop plus a report from our forthcoming reunion. I should also write about the surprise guests we had at the workshop who gave talks or taught for just a few hours. Part 10 will just remain open; you never know what might happen.

Famous person at bottom left

Chuck Palahniuk — or “Chuckles,” as we began calling him before he arrived, perhaps in an effort to defuse his celebrity power — was the most wildly creative of our instructors. Leading the workshop, he took the day’s stories and came out with several ideas for each, some off the top of his head, ways to make them more powerful: this scene could mirror that scene if you change this about the setting, or this object one character carries around could also be used in another instance ironically, or other more powerful uses for motifs and structure. His mind was so flexible; he could invent possibilities for the formal properties of a story so felicitously. If you’ve read Orson Scott Card’s How to Write Science Fiction & Fantasy, you probably remember Card’s “Thousand Ideas in an Hour”; Palahniuk has the same fecundity.

Here’s an example. His week I turned in a short story about a mentally ill son and his mom. The mom wrote poetry with a favorite fountain pen, and during an author reading at a bookstore the son took the pen from her and crazily insisted on writing with it while talking aloud, becoming a social nuisance. Palahniuk pointed out that the pen could explode and cover the son’s arm with Rorschach-like inkblots. The pen is a tool for creativity; the pen, like his mind, breaks; control of the pen is contested, just as control of the son’s life is contested. This was just one of the twenty-something ways he came up with for amping up what was already in my story. Hearing him do this, you couldn’t help but learn some of the ability yourself. Afterward you read real-life stories better too, interacting with people and catching on to their recurring motifs or themes.

I notice the manipulation of formal story properties (character, setting, etc.) a lot while watching TV shows. Lost or The Twilight Zone come to mind. But writing is not contained by formalist wizardy. Sometimes writers just create mood (think of JD Salinger) or just wonder (think of Haruki Murakami) or tell you what’s what (think of Philip K Dick talking about God). And that’s all great, despite the business-like emphasis of some writing instructors on “Make everything in the story perform multiple functions, OMG, we gotta be economical here to turn a profit.” It got on my nerves the way Chuckles constrained everything as if there’s one true way to write. Art and sex are some of the only areas in life where you get to escape rules; people, especially those giving advice, just want to bring rules in because it reduces uncertainty — at the cost of quality and freedom. (Gay Saul Morson’s Narrative and Freedom: the Shadows of Time is a great critical theory book about how traditionally structured narrative clamps down on possibilities and the sense of freedom in fiction.)

He had plenty of rules for sentences, many of which are often totally helpful. Here’s a list of some. (Pam Rentz noted some others.)

- Don’t use “specific” figures like “100 degrees” or “55 mph.” That’s missing an opportunity to characterize. What do those figures mean to the character? Is 100 degrees hot for him or not bad?

- Use lyrical prose as a contrast. Don’t use it often; it gets tiring over time. Use it for effect. [Oh, poo.]

- No abstract verbs: no remembering, considering, etc. [Oh poo again. What if the narrator is an abstract thinker or you are emphasizing uncertainty?]

- No filtering. “I smelled the sour stink of sweat coming off him” should just be “The sour stink of sweat came off him.”[Same poo as above.]

- “Going on with the body”: Go visceral, flesh-and-blood. Describe palms, feet, smells, flavors. Don’t be cliché, but if you don’t do it at all, your narrator will seem disembodied.

- Never/seldom use forms of “to be” or “to have”; use more descriptive action verbs.

- Make your settings (and physical descriptions of people) move. You want a movie, not a framed picture, unless for effect. [E.g., instead of “He wore a black button-down” write “His black button-down came loose from his slacks” or whatever.]

- Don’t shortcut by saying “ugly dress.” Describe the dress and why the POV character thinks it’s ugly.

- Attributive tags for dialogue are good. Not only do they keep the reader clear on who’s talking, they serve as the natural pause in conversation.

- “Submerging the ‘I'”: Circle the pronoun “I” in your manuscript and figure out ways to reduce the use of it. Ideally, use it no more than once per page (!). It reminds the reader the story is not happening to them. Me/my/mine/we/ours do not seem to do this. You can use the word “I” a lot intentionally to create distance.

- Use a lot of dentals: d’s, t’s, p’s, k’s. They sound good.

- Be specific. Is it a maraschino cherry or a Queen Anne cherry or a … A gun is never just a gun.

Here is some other advice he gave to the workshop or to me in the one-on-one conference. Same caveat (from me) as above about “rules.”

- Set specific, measurable, actionable, realistic, timed goals. Big ones. Tell them aloud to each other and everyone else constantly. Hang them on your walls, etc. etc. [I don’t go for this Tony Robbins self-improvement stuff, but here I’m noting what Chuckles said. I believe a person should set goals, but not forced ones. Something like, “I’ll write fiction for two hours every morning.” That’s a lot more human than the bodybuilder obsessive stuff which, I think, ultimately backfires psychologically.]

- Externalize humanity via symbols. We’ll like a horrible character if they have a pet.

- Goal of a first novel: not so much quality as it is to write something people can’t forget. [I believe for art you should not care what other people think while you are creating. But it’s hard to ignore the context you are in.]

- Sell chapters as standalones. Doing so impresses potential publishers.

- Show the reader your (and/or the character’s) authority. Establish credibility via facts, factoids, research, etc., particularly those about the subject of the story.

- You can characterize by making a character habitually notice one thing: e.g., someone’s clothes or money status or whatever.

- Never (!) forward plot through dialogue. Action is always stronger.

- Don’t start a story with thesis/topic sentences that give everything away. One workshop story opened by telling us the character scratched through to his brain. Just show the scratching and make the reader wonder if the character’s going to get to the brain or not.

- A good book: Another Day in the Cerebral Cortex.

- If you bring an object in (a “prop”), use it over and over as many ways as possible. Make story elements do multiple jobs! [Poo. Fiction is not a factory.]

- Setting can’t (!) be stationary and it should influence the character. A fan blows smoke on the character’s face, peanut shells on the bar floor add height to the character…etc.

- Scenes shouldn’t all be the same length. That’s poor pacing.

- Physical action = the strongest way to characterize.

- Putting a lie or an unfulfilled social obligation early in the plot can be useful.

- Check out Victor Turner on limnoid experiences. These are experiences where you go to be a different person, e.g., a cruise ship, a rock concert, Burning Man, etc., where you experience a lot of affection for others, there are social rules in place, etc. People like reading about limnoid experiences, especially invented ones.

- As to research, ask interview subjects to tell you stories. Share your stories so a touchy-feely atmosphere is established. Tape record. Show you’re listening by saying stuff such as: “You’re kidding, they really said _____?” Kind of manipulative but it works.

- It’s okay to write a thousand books and stories with dead fathers in them. [This was in response to a question of mine in the one-on-one conference.]

- Low subject matter in high diction can be comical.

- Check out Cold Comfort Farm and A Confederacy of Dunces.

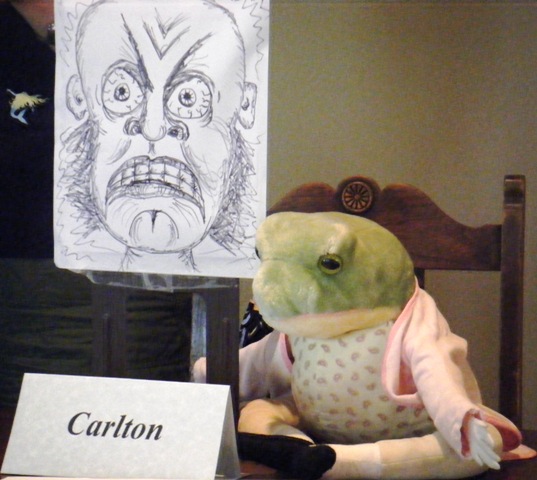

The class gave the instructors gifts, and for Chuck Palahniuk we created something — I can’t quite remember what — that he had to dissect, a fit for his shock jock style. See picture below; here is the complete set.

Dissection

For some reason during Week 6 it was important to me to question Chuckles about his insistence on rules. Not sure why I cared about doing that so much. He did tell me at one point that writers tend to come from one of two backgrounds: journalism or academia. The former are more amenable to rules, he suggested (the miniaturist, Amy Hempel style he prefers). This makes a bit more sense to me now since I’ve sold some journalism pieces and other freelance material; editors want stuff that’s easy-to-read and efficient. But the business mindset shouldn’t overtake art.

Shane Hoversten wrote an amazing story for this final week. It was a farewell story for our class. He included each of us as characters. He imagined me getting drunk at the workshop (I rarely drink), saying stuff about lyrical prose and olfactory sensory details, and passing out. :)

Since the workshop some people have asked me what Chuckles was like as a person. He was reserved compared to our other instructors, who mingled with us more. Probably that was partly because it was his first time to teach at a Clarion; he’s taught at Clarions more since 2008, so I wonder if he socializes more now. He really cared about helping us, and enjoyed teaching. I learned a lot from him.

I’ll write up concluding thoughts about the workshop in Part 9, if I ever get around to it!

Clarion West 2008 – Part 8 of 10 by Douglas Lucas is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License. Based on a work at www.douglaslucas.com. Seeking permissions beyond the scope of this license? Email me: dal@riseup.net.

This post is the eighth in a series of ten about my experiences at Clarion West Writers Workshop (Wikipedia; Twitter) as a member of the 2008 class. I’ll talk about...

January 3rd, 2012 — Clarion-West-2008, Seattle, Space

This post is the seventh in a series of ten about my experiences at Clarion West Writers Workshop (Wikipedia) as a member of the 2008 class. I’ll talk about Week 5 of the workshop, when Sheree R. Thomas (New Book: Shotgun Lullabies; Wikipedia; Blog; NYT piece; NPR talk; Strange Horizons interview) instructed. Here are Parts 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, and 6 of the series. In Part 6 I discussed Connie Willis‘s week (Week 4) and ended by noting my hopes for seeing my Clarionites soon. Indeed, in this post I’ll talk some about the #CW08beach reunion my class held in October 2011!

Sheree attended Clarion West in 1999, a year when, someone said (someone — my notes are unclear), the workshop got intense with pregnancies, people not showing up, manuscripts thrown angrily across the room at their authors, divorces, etc. Clarion’s not really for the faint-hearted; yet, deep-down, writers are faint-hearted folks. So the space station (Clarion West takes place on a secret orbital above Seattle) gets very pressurized.

Happens right here

During her 1999 year, for whatever reason, some students begged Chip Delaney to tell them if they “were” any “good.” Apparently Delaney didn’t want to do that, but eventually acquiesced because his experience as an MFA teacher (if I recall Sheree’s comments correctly) led him to believe it was bullshit to take people’s money for years and just feed them hot air the whole time. Delaney gave students the option of not hearing his opinion. (I’d flip a coin. Because you have to learn not to care.)

Sheree R. Thomas (via)

Early on, Sheree said she wasn’t going to “redline” anybody, because just one person’s opinion doesn’t mean jack, and because there’s no necessary connection between how well someone writes at Clarion and how well they do after Clarion.

How did I do at Clarion West? I wrote two great short stories there (here’s the finished Glenn of Green Gables), one kinda bad story, and grew up a lot, learned stuff. How have I done after? I’ve written 50-something lifestyle/infotainment pieces for CBS News, completed 3 really good new short stories and drafted 5+ more, sold zero of them (though they’ve earned a few Euros through Flattr), and blogged about 100 posts here (also earning a very few Flattr tips). I’m usefully obnoxious on Twitter, where manuscripts don’t fly across the room but subpoenas do; I haven’t earned one yet. It’s all a bit frustrating, though fun. In the time it’s taken me to write these seven posts, I’ve gotten married and am getting divorced; the main payoff of the marriage was growing a spine. Especially now as I live with roommates in a cheap, freezing-cold place that resembles some sort of heavy metal dungeon, and forage for necessary medications like a hunter-gatherer going after berries, I have become downright mean in a way I never anticipated.

Back to Sheree. With the possible exception of Paul Park, she was the most blunt of our instructors, which I thought was great. At “infamous Week 5,” most Clarion classes descend into mayhem. Week 5 took our class and amalgamated it into a giant pile of snuggle. Which mostly was great (see below, our reunion, after all), but the quality of the critiquing by classmates went downhill. Sheree, who’s also a freelance editor, gave me a great tip in our one-on-one conference for getting critiques from people while bypassing the need for them to be any good at giving them. You simply hand them your manuscript and watch their faces as they read it. You see what emotions your story strikes, rather than hear their report about what emotions your story allegedly struck. (Obviously written critiques are useful too, yadda yadda yadda.) We didn’t get to watch Sheree’s face as she read our stories, but we didn’t need to. She was blunt, and appropriately so; one of my favorite instructors there, for sure.

Sheree listed a ton of resources for our class:

Sheree R. Thomas and young person (via)

In response to someone’s story — I forget whose — she suggested the True Porn anthology and the What the Fuck? anthology . She suggested to me Maryse Conde’s novel Crossing the Mangrove and Toni Morrison’s novel Love. When I asked in the one-on-one conference about making secondary characters more autonomous (so to speak), she suggested writing compellingly from the point of view of people who disagree with me would help me create more individuated secondary characters. (Shades of Lacan?)

Week 5 found people guessing about Chuck Palahniuk, the Week 6 instructor, who was the biggest name and biggest wildcard. All the other instructors had either taught a Clarion before or once went to a Clarion themselves — and often, both. But Palahniuk hadn’t done either (though he’s returning to teach in 2012).

Fast forward three years and shift to a sandy orbital above San Diego, where 14 of our 18 classmates showed up for a week-long reunion at a house on (the celestial version of) Mission Beach. That’s more than 75% of the class after three years; that shows some serious bonding. (And our email list is still active.) Our venerable classmate Pam Rentz organized the whole thing — a herculean effort for which we rewarded her with a gift that included a signed picture frame. We all got along really well at the reunion, though the trippy reunion vibe was slightly present, as at all reunions. Same people, but different, but same, so who am I? That kind of thing. We all had dinner together most nights at this huge dinner table. Small groups of us also did some in-person crit sessions, which was really cool.

This place rocked!

What happened there stays there

(Yours truly in black)

Silly as ever!

You can find more CW08beach reunion pics at Pam’s dropbox.

I’m not sure what to conclude about my writing progress since Clarion West 2008. Though I haven’t finished much fiction, I feel good about my writing overall, but then again, I’m intrinsically an optimist. It’s reassuring to remember Cory Doctorow talking during Week 3 about it taking him several years after his Clarion West student year to finish a lot of fiction. But I don’t have to conclude yet; I still have 3 more posts in this series to go!

Clarion West 2008 – Part 7 of 10 by Douglas Lucas is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License. Based on a work at www.douglaslucas.com. Seeking permissions beyond the scope of this license? Email me: dal@douglaslucas.com.

This post is the seventh in a series of ten about my experiences at Clarion West Writers Workshop (Wikipedia) as a member of the 2008 class. I’ll talk about Week...

October 25th, 2010 — Clarion-West-2008, Seattle, Space

This post is the sixth in a series of ten about my experiences at Clarion West Writers Workshop (Wikipedia) as a member of the 2008 class. I’ll talk about Week 4 of the workshop, when Connie Willis (Wikipedia) instructed. Here are Parts 1, 2, 3, 4, and 5 of the series. In Part 5 I discussed Cory Doctorow‘s week and ended with a somewhat bizarre dismantling of my psyche. This post is quite the opposite: I brag. Bear with!

“Total exhaustion is the goal,” Mary Rosenblum said, teaching Clarion West during our Week 2, and by Connie’s Week 4 I was totally exhausted; that’s clear to me now as I read over the emails I sent friends and family during that middle of July ’08. In those emails I also now detect a down-on-myself attitude about my fiction-writing, one that I don’t particularly experience anymore (knock on wood). These days I get dejected or grumpy about my fiction-writing at times, of course, but I don’t feel such negativity, pessimism, or bewilderment about the whole process. I have strong confidence in my abilities, and faith that new stories will turn out right eventually, that I’ll be able to revise them into artworks I’m proud of. That confidence is due in part to Wifely Kate, additional and diverse employment experiences, and other factors; but, a huge chunk of it has definitely come from Clarion West. This benefit from Clarion West took a long time to set in; I’ve had to incorporate what all I learned into my writing and my life, and that took me quite a while.

Outside the Clarion West spaceship: replica of Seattle

The additional confidence from Clarion West hasn’t derived so much from the grab-bag of tips I picked up from the instructors or my fellow students (though these have helped!), nor was it any sort of confirming validation that other Clarionites sometimes mention. I gained so much, I think, from the way a Clarion workshop primarily focuses on the process of revision, not creating an ultimate and spotless draft; and, second, making weird friends who accept me for my weirdness-es was an invaluable gift. As Kate puts it, I found my people, my tribe.

About Clarion’s focus on revision — writing and life are pretty much driven by storytelling, or at least by motifs that recur and recur, carrying with them their old meanings and acquiring new ones as they go. I’ll have more to say about how this works when I get to my Week 6 post (the forthcoming Part 8), but for now, the emphasis on revision, the way instructors and fellow students took specific elements of stories and suggested specific changes (with reasons!), gave a real sense that one’s own fiction can work, after all, that the poor draft you wrote does indeed have potential in it. There’s a real feeling of hope there.

Which is why I shouldn’t have been so down on myself. My Week 4 short story was an unfortunately convoluted mystery. I came up with the story from absolute scratch — not even a vague idea of the story before the workshop — which was a specific challenge I’d set myself before arriving at the space station (the Workshop mysteriously floats in orbit over Seattle). In the emails, instead of feeling glad I about actually succeeding at this task I’d set myself, I was all down on how the story didn’t “work.” Well, pretty much no first draft ever works. And, no matter how bungled, the first draft had cool ideas. Why be so negative?

Connie told us it took her eight years of writing before she sold a story; she also asked each of us to tell the group how we started writing. The answers varied; some knew since birth, it seemed, and others were late bloomers. Me? I wanted to be a writer as a kindergartner, but soon switched my hoped-for career to astronaut; in middle school I made up stories often, but then switched to music. When for various reasons I determined a music career was not for me, I tried writing again, and after a few months, maybe even only after a full year, I began to enjoy it. I hope people reading this who are searching for their own directions, whether as a writer or otherwise, come to feel patient with their search. Often — and the psychologist Csíkszentmihályi (gloriously pronounced “Chick-sent-me-high”) makes this point — it can take learning time before you enjoy a career path. For many, beginning to play, for example, tennis (maybe at the behest of a friend) isn’t very fun: all those frustrating, misguided racket swings and terrible serves. But once you can get to where you can actually play not too shabbily, the fun and satisfaction finally starts setting in. If you give up on a career path without giving yourself time to get some basic proficiency, you probably haven’t really tried at all.

More about Connie. She’s a frequent master of ceremonies at science fiction & fantasy events, a respected dame in the field. She was one of the instructors who hung around our quarters of the space station in her spare time, answering questions and just visiting. Before I went to the Workshop, I read one book by each instructor; for her I selected Passage. The book was fast-paced and straightforwardly written — and also very moving. Highly recommended. She’s a real expert at plot.

Her advice mostly centered on plot, too. Here are some of her tips I collected; she gave the caveat that her advice was only her advice, that we should feel, like Agatha Christie, free to break any rules.

But I should note first that during Week 4 an anonymous friend sent me a replacement copy of Peter Straub‘s If You Could See Me Now; the copy I brought with me, oddly, was missing a page. I found it helpful to have a book with me that was totally unrelated to Clarion West. Really reading it was impossible, due to the total exhaustion, but being able to dip into a page here or there and disappear from the Workshop was refreshing.

Anyhow: tips from Connie Willis:

-

Connie’s definition of plot: “A constantly surprising chain of events with each new scene turning the story to a new point where the logical occurs, unforeseen by the reader.”

-

Unremitting horror exhausts readers. Use contrast!

-

The perfect title means one thing when you start the story, and by the end of the story, it means another. It should be evocative, it should add something to the story, and it should have both literal and figurative meaning(s).

-

PG Wodehouse claimed a 7500 word story needs two big reversals: one at 1500 words, one at 6000 words.

-

If some things in the story are complicated, make other things simple.

-

Develop a good filing system (for research and ideas, e.g.)!

-

Fix one aspect at a time when you revise.

-

When you read fiction or watch film, look for reversals, raising the stakes (“things get worse”), foreshadowing, climax, dénouement, interior conflict, exterior conflict. Study extensively the books you know well and admire.

Connie also gave us each a critique coupon to snail-mail her along with a short story or novel opening, if we wanted. Finally, a tidbit: in interviews she’s mentioned that when she was very young, she read the fiction section at her local library in alphabetical order. At the space station I asked her how far she made it through the alphabet. I believe her answer was H, that reading Heinlein made her switch to reading all the library’s science fiction.

As I’ve said throughout this series, writing these Clarion West posts induces in me a unique sort of stress that I don’t fully understand; I feel, maybe, as if I’m just not describing the time well enough, not at all portraying just how transformative and wonderful the Workshop was — that these posts are somehow doing violence to a great gestalt from a time that’s gradually starting to feel like long ago. Maybe that’s why I delay these posts: to hang on to my Clarion West experience.

One thing that continues on, however, are my classmates, our relationships. They’re all people I treasure; mostly we keep in touch, sometimes through our email list, sometimes with individual phone calls, even trips here and there.

One way or another, see y’all special Clarionites soon. ;-)

This post is the sixth in a series of ten about my experiences at Clarion West Writers Workshop (Wikipedia) as a member of the 2008 class. I’ll talk about Week...

April 24th, 2010 — Clarion-West-2008

This post is the fifth in a series of ten about my experiences at Clarion West Writers Workshop (Wikipedia) as a member of the 2008 class. I’ll talk about my third week at the workshop, when Cory Doctorow (Wikipedia, Twitter; freely downloadable recent novels Little Brother and Makers) instructed. Here’re Parts 1, 2, 3, and 4 of the series. In Part 4 I discussed writing my story “Glenn of Green Gables” and ended with a cliffhanger: aliens had just broken into our space station hull.

This post is the fifth in a series of ten about my experiences at Clarion West Writers Workshop (Wikipedia) as a member of the 2008 class. I’ll talk about my third week at the workshop, when Cory Doctorow (Wikipedia, Twitter; freely downloadable recent novels Little Brother and Makers) instructed. Here’re Parts 1, 2, 3, and 4 of the series. In Part 4 I discussed writing my story “Glenn of Green Gables” and ended with a cliffhanger: aliens had just broken into our space station hull.

As mentioned before, Clarion West is stationed in geosynchronous orbit above Seattle, but at the same time it replicates the Earthly city below. I think this Miévillean metaphysic serves in part to shield Clarionites’ dubious deeds from those who might not understand what happens when writing workshops (rightfully) push people to revise their stories: their fictional stories and moreso their personal identity ones. In the space station, as narratology becomes conscious craft, students confront fictional characters who battle through fictional plots, and confront seventeen other writers, plus a vaunted instructor, each of whom are battling through their personal plots — and everyone winds up using the manuscripts as materiel.

Mortal Kombat II: SNES

With their laptops students type out art, trails to their selves; the art becomes in the classroom terrain for proxy wars over personal identities — and over the group’s identity, too. Everyone in the building is at once enemy and comrade. Reality shows would pay to sell some of the behavior that bubbles up. Caught in it, students lean on each other for support. That requires privacy; thus the mystery of the workshop’s location. Again: the experience requires privacy. To have four laptops — writers’ trusted weapons — stolen by aliens breaking in … an invasion!

I’m not clear on the actual details of the heist, none of us were, though we scried far and wide for the aliens, and sent many spaceships chasing after. We were all as one laptop-less ragtags, but within forty-eight hours we were high-fiving each other — because to our quick rescue came an advocate of privacy shielded with a sheen of transparency, in other words, that frenetic pirate known as Cory Doctorow.

Info he finds useful he boomerangs, and so when he learned aliens invaded just prior to his arrival, he donated his instructor’s pay toward laptop replacements and posted the following on Boing Boing:

Clarion West, the famed Seattle science fiction workshop, has suffered a terrible theft: four student laptops were stolen yesterday. Clarion West (like Clarion in San Diego) is a grueling, six-week intensive boot-camp for science fiction writers. Students often quit their jobs and save for years to attend and it goes without saying that they can hardly absorb the cost of a new laptop in the middle of the workshop.

I’m flying to Seattle tomorrow to teach the third week of the workshop and I’m keenly aware of the chaos this will have wrought on the students. The workshop’s organizers are soliciting donations — either hardware or cash — to get the students up and running. The workshop is incorporated as a 501(c)3 charity, so any donations are tax deductible.

I am donating all of my teaching fee to the fund. I hope that some of you will be moved to chip in whatever you can afford, to help fund the instruction of the next generation of great science fiction writers.

Clarion West received enough donations to replace all stolen laptops. I wonder which literary fiction communities could boast the same (I’m actually asking!).

That week, in addition to the invasion, I was shaken “as if with ague,” which is the writerly cliche for describing someone tremoring.

Except there was no as-if subjunctive for me: all week I had a constant fever registering over a hundred, and I had a cough, too. I think the illness was brought on by too much exercise (I ran in the mornings). Thankfully the administrators (Neile Graham and Les Howle) gave me nothing but the kindest help. My memories of Cory’s week, though, remain hazy.

Still I can report some of Cory’s instruction. An advocate of privacy, I said; Cory, who’s associated with the Electronic Frontier Foundation (Twitter), has a number of controversial views not just on privacy but also on piracy, file-sharing, DRM and media industries, more. Some of his afternoon lectures covered his digital ideology. I remember him as a fast-talking firebrand.

All the same he had a sensitivity about him that I don’t see many mention. For example, he was the only instructor who in the one-on-one sessions made a point of asking how we were doing emotionally, aside from the writing portion of the workshop; that thoughtfulness probably was in part due to his having attended Clarion East as a student in 1992. He definitely understood how stressful and transforming the entire experience is, how it requires the privacy and the care that can come with a good group’s special, monastic space (station).

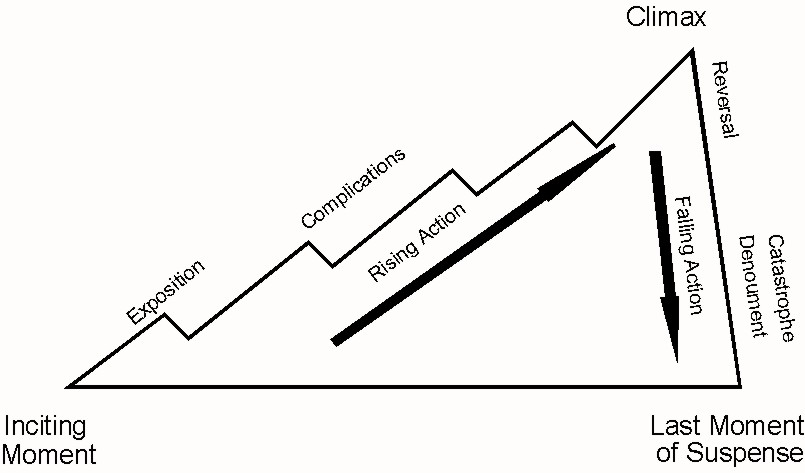

In one lecture Cory gave us a seven-point formula for plotting: create 1) a character 2) in a place 3) with a problem 4) who intelligently overcomes obstacles, 5) and as things get worse, 6) conflict by necessity comes to a climax, 7) after which there’s a denoument.

If I’m not mistaken, Cory portrayed this formula as universal, which with if so I take issue. The formula doesn’t account for certain types of good stories that go under-represented in science fiction & fantasy: stories with unreliable narrators, trapped protagonists who don’t escape into heroic stature — they’re the kind of characters who remind us, as we watch their ironies, of just how much sway our environment has over our lives, and how unreliable information is, no matter how much we try to route around those bugs/features of reality.

As I mentioned in Part 4, most (all?) my classmates in the space station, along with our Week 2 instructor (Mary Rosenblum), totally loved my Week 2 story (“Glenn of Green Gables“); Cory was among the readers who didn’t. Years later I can count the non-fans on one baffled hand. Cory argued Glenn isn’t like-able since he doesn’t solve his problems intelligently. My rejoinder, however unnecessary it is now (people are entitled to their opinions!), is the one a fellow Clarionite suggested: Glenn is an emotionally intelligent problem-solver because he bravely sticks to his lonely love for ol’ Anne Shirley despite increasingly sinking circumstances…

I've never actually read any Green Gables books -- just Googled 'em for allusions

Maybe I seem bitter, and for a time I did feel a bit (byte?) uselessly resentful. But that’s not the point, not me; the point is to tell you (especially future Clarion students) what I experienced. So: there were three male instructors my year, three female. My father is and has been, uh, conspiciously absent from my life, and so the less mature 2008 version of me unconsciously scrutinized Paul Park, Cory, and Chuck Palahniuk in a way he didn’t the three other instructors (Mary, Connie Willis, Sheree R. Thomas). I regarded the men’s instruction as having a sort of paternal absolutism to it.

And so I’m like…

Now that I’m more of an “active protagonist” in my “real” life (thanks in no small part to Clarion West and Seattle), I’ve intentionally challenged myself to write short stories in different and also more traditional ways, and for that, Cory’s obstacle-tackling pointers have proven handy.

…where am I?

One application: while plotting with point 5 — “as things get worse” — I can ask myself, not “what happens next?” but rather “what would raise the stakes?”

But mostly I just keep piracy and capering as tesserae in my own aesthetic.

You want more? Here’s a list of Cory’s excellent fiction-writing advice:

- If you don’t like your story, you get stuck more frequently. If you’re stuck, ask yourself what you need in the story to make yourself like it.

- Use a feed reader and consider staying on top of interesting things (including current events) part of your writing job. But be willing to “mark all as read” when you get behind; don’t be perfectionistic about it, or you’ll never keep up with anything.

- If you’re really stuck, changing projects can be a good strategy.

- Write down little bits of things that interest you, and have a good storage system.

- Get away from any ceremonial ritual for writing. You will become dependent on the ritual.

- Freewriting about whatever is blocking you works well. The shortest path between thought A and thought B, according to some science article or other, is writing it down.

- Subjunctive sentence constructions, dreams sequences, telephone conversations, &tc. generally don’t have as much power as showing situations actually happening to characters face-to-face.

- Time management: use Getting Things Done.

- When you’re stuck, look back at what you wrote earlier. You’ll often discover or remember stuff you were thinking earlier that you can use to go forward.

- Use descriptive filenames if guidelines for electronic submissions ask for attachments.

- The central conceit of a story sometimes doesn’t even show up until a story has gone through multiple drafts. Be willing to revise extensively.

- You stop having writer’s block when writing becomes your job.

- The main thing is believing in yourself.

This post is the fifth in a series of ten about my experiences at Clarion West Writers Workshop (Wikipedia) as a member of the 2008 class. I’ll talk about my...

January 14th, 2010 — Clarion-West-2008

This post is the fourth in a series of ten about my experiences at Clarion West Writers Workshop (Wikipedia entry) as a 2008 class member. I’ll talk about the workshop’s second week, when Mary Rosenblum instructed. Here’s Part 1, Part 2, and Part 3 of the series. I ended Part 3 with a picture of Clarionites sailing away from the workshop’s secret space station (in geosynchronous orbit above Seattle) to acquire beer.

This post is the fourth in a series of ten about my experiences at Clarion West Writers Workshop (Wikipedia entry) as a 2008 class member. I’ll talk about the workshop’s second week, when Mary Rosenblum instructed. Here’s Part 1, Part 2, and Part 3 of the series. I ended Part 3 with a picture of Clarionites sailing away from the workshop’s secret space station (in geosynchronous orbit above Seattle) to acquire beer.

Sailing pretty much dominated my mind that week, though it was sailing of the oceanic variety. I was writing my first story for class critique, “Glenn of Green Gables,” which in 2009 I released under a Creative Commons License, so go read it! (A bit of DFW.com publicity about me as a group of four local artists inspired the CC licensing.) The story’s about a crossdresser on a cruise ship who navigates through a love triangle.

Writing “Glenn” made me incredibly nervous. You normally don’t hand a bunch of roommates who are semi-friends, semi-strangers 20-odd copies of 6200 first-person words concerning sex. I’ll confess that my worries notwithstanding, I felt quite haughty those first two weeks, confident that “Glenn” was quite good and confident that some stories turned in by others weren’t. (Little did I know I too would turn in poor stories later.) However, I had no idea what people would assume about my own underpants. Frequently I scuttled into the neighboring dorm room where my friend Pritpaul stresslessly studied Canadian hockey scores, and he reassured me all would be well: no one would pull down my pants without asking first. [/caption]

[/caption]

While writing, I periodically updated the dry-erase markerboard hanging outside my dorm room with enigmatic phrases from the story, phrases completely devoid of context. (Future Clarionites: my year, each dorm room had a markerboard outside the door, but they didn’t come with any markers.) So classmates saw such phrases as: “a dolphin perhaps”; “spread gossip about me on the Internet”; “Stallone. Van Damme.”; “Lights brighter than Christmas”; “headed toward Quebec.” People tried to guess what my story was about, and that was pretty amusing in and of itself. Classmate Christopher said my markerboard was giving him story ideas.

About that confidence — one classmate, Caren, said “Glenn” completely thwarted her expectation that I’d turn in something broody. She also pointed out, correctly, that “the Douglas show” was going on constantly in my gear-turning head. I’ll just say that these days I no longer tune in only to myself, and that my Clarion West experience had a lot to do with that. The workshop made me scrutinize other’s narratives and interact with them in person daily; that in part was what raised my general self- and other-awareness.

Looking back at the emails I routinely sent home from the space station, I see that by the start of the second week I already wrote Life here is starting to blur into one endless day, so it’s hard to remember what happened when. That’s ever more true now; writing this is agonizing: everything I post about Clarion West seems utterly banal compared to that summer. A few months back a dental hygienist was scraping her sickle scythe across my gums, and it hurt so bad — as it went, the thing made crunch noises. The hygienist told me to think of my happy place. Well, that was Clarion West.

Pretty much the entire class loved “Glenn,” as did our instructor that week, Mary Rosenblum. Mary attended Clarion West herself in 1988; here’s her site, her blog, her Wikipedia entry, an excerpt from the interview Locus Magazine conducted with her, and the opening of her awesome story “Lion Walk,” published in January 2009 by Asimov’s. You might know Mary by her sometimes (open) pen name, Mary Freeman, which she used to write the Gardening Mysteries series.

Pretty much the entire class loved “Glenn,” as did our instructor that week, Mary Rosenblum. Mary attended Clarion West herself in 1988; here’s her site, her blog, her Wikipedia entry, an excerpt from the interview Locus Magazine conducted with her, and the opening of her awesome story “Lion Walk,” published in January 2009 by Asimov’s. You might know Mary by her sometimes (open) pen name, Mary Freeman, which she used to write the Gardening Mysteries series.

Here’s some of Mary’s wisdom, according to the paraphrases in my notes. Hopefully I won’t misrepresent anything she said.

- The stuff you write when you feel you’re writing poorly is basically as good as the stuff you write when you feel you’re writing well. Keep writing even when you feel you’re writing poorly.

- The fiction market is undergoing radical changes. Stay on top of electronic publishing.

- Show characters’ opinions on settings. This is one way to sneak in backstory.

- Watch people’s body language in real life. A lot.

- WHY WHY WHY. You need to figure out your characters’ motivations, the worldbuilding details, everything. You might not end up explaining them in the story, but never be vague on them yourself.

- Sometimes showing very (physically) small details evokes a lot of emotion.

- Mary’s Rule of Three: each scene should deepen character, enrich setting, thicken plot.

- Exercise: Walk into an unfamiliar space, look around for no more than 30 seconds, walk out, and write what you remember–and write an additional take from your character’s POV. Such a description will often give you more emotion than if you’d meticulously observed the setting. Worst are “catalogue” settings (“there were 3 chairs, 4 light bulbs…”)

In the one-on-one conference, Mary was very complimentary, and her words inspire me to this day. The one-on-one conferences, oddly perhaps, were one of my favorite aspects of the workshop, and I feel I learned quite a lot in them.

Now, the workshopping vibe. Probably Clarion West should take thickness measurements of people’s skin before and after the summer. I toughened up a lot. Also I learned a lot about tact. There are people who busily pat themselves on the back about how they give such ‘brutally honest’ opinions, but that usually makes the critiqued person shut out the critiquer. You can dish it out effectively and respectfully without being a brute. Takes practice, though. The flip side of this: by Week 6 I for one — and maybe only for one — felt that our class had descended too much into lovey-dovey softness. That might have been something idiosyncratic to our class, though, because even the administrators pointed out that our class all got along startlingly well. Most of the time. Sociologists would love Clarion West: a little bit of Zimbardo, a lot of Elysium. Like a reality TV show — only it’s actually real.

Now, the workshopping vibe. Probably Clarion West should take thickness measurements of people’s skin before and after the summer. I toughened up a lot. Also I learned a lot about tact. There are people who busily pat themselves on the back about how they give such ‘brutally honest’ opinions, but that usually makes the critiqued person shut out the critiquer. You can dish it out effectively and respectfully without being a brute. Takes practice, though. The flip side of this: by Week 6 I for one — and maybe only for one — felt that our class had descended too much into lovey-dovey softness. That might have been something idiosyncratic to our class, though, because even the administrators pointed out that our class all got along startlingly well. Most of the time. Sociologists would love Clarion West: a little bit of Zimbardo, a lot of Elysium. Like a reality TV show — only it’s actually real.

Here are some quotes classmates uttered in the course of Week 2’s critiquing.

- “I hated the main character. I wouldn’t let this guy clean the city’s latrines.”

- “Should you build in redundant systems in case of reader failure?”

- “Heal myself or heal this guy? F*** him!”

- “Women are all the time going home with men they shouldn’t be going home with.”

- “So, why does he give her life? Is he just a warlock d***ing around with nothing else to do on a Sunday night?”

- “I was waiting for the speculum to be busted out — I don’t necessarily know what a speculum is.”

At the end of the week, we all attended our second party; everybody attends a party each workshop weekend, even Week 6. The parties were fun; some socialized more skillfully than others. All was lovely. But the next week,

aliens broke into our space station’s hull …

This post is the fourth in a series of ten about my experiences at Clarion West Writers Workshop (Wikipedia entry) as a 2008 class member. I’ll talk about the workshop’s...

August 30th, 2009 — Clarion-West-2008

This post is the third in a series of ten about my experiences at Clarion West Writers Workshop in 2008. I’ll talk about the first week of the workshop, when Paul Park instructed. Here’s Part 1 and Part 2 of the series. I ended Part 2 by saying that at the mysterious space station in geosynchronous orbit above Seattle, where the workshop is held, I started the first week proper by thinking about characterization.

This post is the third in a series of ten about my experiences at Clarion West Writers Workshop in 2008. I’ll talk about the first week of the workshop, when Paul Park instructed. Here’s Part 1 and Part 2 of the series. I ended Part 2 by saying that at the mysterious space station in geosynchronous orbit above Seattle, where the workshop is held, I started the first week proper by thinking about characterization.

Seattle, far below the space station

Because characterization is what Paul Park began by talking about.

Paul, a tall, fit guy, struck me and others as confident and intense. Among other books, he’s written the Roumania Quartet novels and the short story collection If Lions Could Speak. He seemed very much a ‘thinker’, and that partly explains why I could easily relate to him and what he had to say. Since it was only the first week of the workshop, no one had turned any stories in; so, instead of the Milford story-critiquing method that drove the workshop through weeks 2 to 6, Paul lectured — mostly in a Socratic way. Sometimes he used exercises he asked us to hand in as the basis for his lectures.

Paul Park, standing left, Clarionites in the foreground

Paul said that on the whole, our Clarion submission stories, while packed with whizbang ideas, didn’t make him invest in the characters strongly enough. So throughout the week he gave us a bunch of tips about characterization and other aspects of fiction-writing. I can tell you without looking at my notes what tips Paul gave that stuck with me the most. Bear in mind I’m paraphrasing.

- Story events happen because of the way people (the characters) are; writers shouldn’t just construct plots and then shoehorn characters in.

- Compressing the timespan of a short story can often give it more ‘kinetic energy.’ Classical unities and whatnot.

- Too frequently, writers use point-of-view characters’ physiological reactions as a shortcut attempt to convey emotion. For example — and this my example, not Paul’s — all too often writers trying to evoke, say, fear, strew sentences such as “Her scalp tingled” and “Her scalp prickled” and “Her scalp tightened” across even just a single short story. The physiological reactions become unintentionally comical (or annoying) tics. You start to wonder if the scalp-y character simply needs a different type of shampoo. The best book I ever read about representing emotion in fiction without resorting to cliches, by the way, was Ann Hood‘s Creating Character Emotions. I have no idea why that book doesn’t get more attention. Most fiction-writing books are nearly useless; Ann Hood’s isn’t.

- Many writers, trying to convey what secondary characters feel, rely far too much on simply reporting the characters’ facial expressions. Sometimes that’s necessary, but conveying what secondary characters feel is (often) a lot more effective when the characters simply do things. Example — and again this is my example, not Paul’s — instead of “her eyes were ablaze with anger” why not “she picked up the baseball bat and pointed its business end at me as though the bat were a sword”? To me, fictional facial expressions are the most obnoxious when writers use eyes to relay to readers what secondary characters feel. How many times have you read “Her eyes were ablaze with anger” in your favorite airport novel?

Sometimes in real life people do communicate startling things exclusively with their eyes, and it’s such an intense experience that cliche sentences don’t do it justice. Oh, and check this out, the study of eye contact is called oculesics. I gotta learn more about them thar oculesics, but I can’t find much written on the subject, can’t find any sort of expert oculesics-ist (or whatever). So for now I simply stare at people and ask them what we’re feeling. People don’t take it too kindly.

The collection of fiction-writing tips I come home from the space station with wasn’t at all the point. The entire workshop process improved my writing and me in ways a list of tips can’t convey. The whole process seemed a sort of artsy group therapy, centered around words and storytelling, both of which have a great deal to do with how people mature and generate meaning. Somewhere therein lies the key to what Clarion West meant. At the time, though, I was far too busy to ask myself what the heck Clarion West was adding up to — the Apollo astronauts generally say the same thing about when they went to outer space: ‘We were too busy picking up rocks and setting down experiment packages to write poems about our feelings.’

Clarionites, taking a break from critiquing stories, go out for beer

This post is the third in a series of ten about my experiences at Clarion West Writers Workshop in 2008. I’ll talk about the first week of the workshop, when...

May 1st, 2009 — Clarion-West-2008

This post is the second in a series of ten about my experiences at Clarion West Writers Workshop in 2008. I’ll talk about the weekend I spent there just before the workshop began in earnest; it was the weekend of the 2008 Locus Awards and the 2008 Science Fiction Hall of Fame Induction Ceremony. Part 1 of this series is here. I ended Part 1 with my blast-off to the mysterious space station in geosynchronous orbit above Seattle, where the workshop is held.

This post is the second in a series of ten about my experiences at Clarion West Writers Workshop in 2008. I’ll talk about the weekend I spent there just before the workshop began in earnest; it was the weekend of the 2008 Locus Awards and the 2008 Science Fiction Hall of Fame Induction Ceremony. Part 1 of this series is here. I ended Part 1 with my blast-off to the mysterious space station in geosynchronous orbit above Seattle, where the workshop is held.

As American Airlines rocketed me out of Earth’s atmosphere, I read Peter Straub’s 1977 novel If You Could See Me Now — until I discovered the paperback was missing a page. Which wasn’t at all unnerving. Everything else was packed perfectly, and I had a journal in hand. Everything, I was convinced, would turn out right. The places I’d go!

As American Airlines rocketed me out of Earth’s atmosphere, I read Peter Straub’s 1977 novel If You Could See Me Now — until I discovered the paperback was missing a page. Which wasn’t at all unnerving. Everything else was packed perfectly, and I had a journal in hand. Everything, I was convinced, would turn out right. The places I’d go!

The space station’s docking bay looked exactly like Sea-Tac Airport. Pamela Rentz, a fellow Clarionite (that is, Clarion student), waited patiently outside the airport to pick me up. I found her, and she drove herself and me to the workshop dormitory. The entire trip, we pretended not to be nervous..

At the dorm, the fantastic Neile Graham, one of the two administrators (the other is the equally fantastic Les Howle), welcomed us. Neile gave us the basic what’s-up, then left us to pick our rooms. I quickly nabbed the largest one (which was on the top floor); I like a lot of space for my busy mind to stretch out. There was indeed a lot of space: two large closets, nine chests-of-drawers, no joke! The only disadvantage was the heat pouring in through the long many-windowed wall. I figured, though, that the room couldn’t get any hotter than my home state, Texas. Also I realized I’d be on the side of our dorm nearest the rowdy frat neighbors, but as it turned out, their late-night drunken war-whoops never bothered me. I like zoology.

Next I explored the dorm. A Lovecraftian maze. Passages winding around, staircases leading nowhere … I exaggerate, but just slightly. Once Clarionite An Owomoyela arrived, she stuck Post-It notes — such as the one pictured here — on several of the doors in order to signal which room was which. The notes remained in place all six weeks, thank God, because they helped me see my destination through the gauze-of-exhaustion vision that Clarion inflicts.

After my reconnaissance, I made haste to seize as many items from the administrators’ stash as could possibly help me. First and foremost: fans. The majority of Seattleites are air-conditioning atheists, a belief system quite unfamiliar to me. Some nights my room would become so sticky and sweltering with heat that I’d wake up sweating. We have muscular heat ourselves in Texas — most of us just don’t prefer to sleep in it. The fans helped, some; I had my family ship me two small Honeywells to add to my fan fleet.

That brings up a point. My family shipped me the fans because I had little free time. Which was great: I was there to work. But some of my friends never grasped the workload Clarionites experience. (“Why didn’t you see such-and-such in Seattle?” they still ask.) Weekdays we’d closely critique about 15,000 words of stories — about 50 pages of a trade paperback — at the same time as we wrote our own stuff. That doesn’t count class, the optional lectures, the once-a-weekend parties, the all-important middle-of-the-night discussions in the hallway about Faulkner (hi, Jim!) or Theodore Sturgeon (hi, Owen!) or Ray Bradbury (hi, Pritpaul!) … Some found time to goof off — watching Flight of the Conchords was quite popular, for some reason unbeknowst to my all-too-serious mind — but for the most part, I didn’t get much goofing done. I worked harder at Clarion than I did earning my BA (and I earned rather good grades in college).

One thing I grabbed from the administrators’ stash was a personal printer. We emailed copies of our stories to Kinko’s for mass printing, and the dorm had a functional network printer I could have used if I really needed to, but for psychological comfort, I wanted a printer in my own room. I tend to print my writing a lot, to make notes and corrections by hand. Future Clarionites of similar psychological persuasion: when you get there, grab a printer from the stash, quick!

That Friday, the Clarionites who’d already arrived went to The Ave — a shop-lined street in Seattle’s University District. Ah, Seattle, now my favorite city; of course, I view it with extremely favorable bias. I’m not sure how to adequately synopsize the effect that living somewhere other than my familiar Texas had on me. Travel does not give you the same experience. Living in Seattle I learned firsthand how many other possibilities there are in the world, and how people elsewhere take different things seriously — and aren’t necessarily ostracized for it. Even the small things: in Fort Worth, I carry a book with me, and strangers at best ask if I’m in school; in Seattle, it’s not uncommon to see others carrying books (the picture below shows the fiction magazine section at a small shop — I remember they had, for example, Cemetery Dance). Six weeks living in Seattle aged me mentally six million years for the better.

That Friday, the Clarionites who’d already arrived went to The Ave — a shop-lined street in Seattle’s University District. Ah, Seattle, now my favorite city; of course, I view it with extremely favorable bias. I’m not sure how to adequately synopsize the effect that living somewhere other than my familiar Texas had on me. Travel does not give you the same experience. Living in Seattle I learned firsthand how many other possibilities there are in the world, and how people elsewhere take different things seriously — and aren’t necessarily ostracized for it. Even the small things: in Fort Worth, I carry a book with me, and strangers at best ask if I’m in school; in Seattle, it’s not uncommon to see others carrying books (the picture below shows the fiction magazine section at a small shop — I remember they had, for example, Cemetery Dance). Six weeks living in Seattle aged me mentally six million years for the better.

On The Ave, at whichever restaurant it was that we chose, we made nervous conversation (well, at least I felt nervous). I suggest to any future Clarionites, get to know everyone in your group! De jure and ex cathedra: you’re all a bunch of lovable weirdos. =)

If I remember correctly, it was later in the day that Locus held their 2008 Awards ceremony at the Courtyard Marriott Hotel, and most of us Clarionites attended, wearing, like most everyone else, the event’s traditional embarassing Hawaiian shirts. Then, we went to the University of Washington campus, where Nancy Pearl interviewed William Gibson, an event well-blogged by Brenda Cooper here. After that, a Clarion West reception. There David G. Hartwell told me a tidbit about Theodore Sturgeon teaching at Clarion East in, I believe, 1970: according to Hartwell, Sturgeon said a good way to start characterizing fictitious characters is to think about their professions and how they spend their typical days.

Which is exactly what I started thinking about as Clarion West 2008 began.

This post is the second in a series of ten about my experiences at Clarion West Writers Workshop in 2008. I’ll talk about the weekend I spent there just before...

December 27th, 2008 — Clarion-West-2008

This post is the first in a series of ten about my experiences at Clarion West Writers Workshop in 2008. Clarion West is an intense six-week writers’ workshop held at a mysterious space station in geosynchronous orbit above Seattle. Writers live in the station over the course of the workshop.

My year Paul Park, Mary Rosenblum, Cory Doctorow, Connie Willis, Sheree R. Thomas, and Chuck Palahniuk instructed. I’ll post two entries (counting this post) for just before Clarion West, one for each of the six weeks I spent there, and two for just after what turned out to be the best experience of my life (so far!).

During my final semester at my alma mater, TCU, one of my profs, Neil Easterbrook, handed me a flier for Clarion West. He knew I’d taken creative writing classes and that I enjoyed speculative fiction (a vague umbrella term for science fiction, fantasy, horror, etc. — whatever those labels mean). I’d heard of the Clarion West Writers Workshops — there’s three: East (San Diego), West (Seattle), and South (Brisbane) — from the Web and from Orson Scott Card’s How to Write Science Fiction and Fantasy. Card writes that a Clarion workshop:

isn’t for fragile people. It’s a tough experience […] If you’re just starting out and completely uncertain of your identity as a writer, Clarion can be the end, not the beginning. But if you know you’re a writer, […] apply to Clarion.

Well, I knew I was a writer, but I was also timid. I’d written fiction for only two years, and only completed about ten short stories! How the heck could I complete a short story every week for six weeks? And possibly more, depending on the instructors? Not to mention I was unaccustomed to travel. How could I manage six weeks in a space station with writers undoubtedly more talented than I?

Neil encouraged me, as did Cynthia Shearer. (Which goes to show the importance of surrounding yourself with good, positive people.) So I carved a 29-page short story out of novel-in-progress; application manuscripts couldn’t go over 30 pages. I don’t believe I slept the last 48 hours before the deadline. Revising, revising, revising. I emailed my application off at the last minute.

For future applicants’ reference: my application story had no speculative elements. During our workshop, a few people did write some non-speculative stories.

For future applicants’ reference: my application story had no speculative elements. During our workshop, a few people did write some non-speculative stories.

What do you know: in March I received The Call — Clarion West notifies successful applicants by phone. At first I figured The Call was actually A Prank Call. Once I realized it wasn’t, I calmly explained I’d jump up and down after shock wore off. =p

Over the next three months, my nerves popped away. My biggest anxiety: six-plus stories, six weeks, how?! The info packet said we couldn’t bring trunk stories. Rightfully so. For one, the no-trunk-stories policy makes everyone equally anxious! =p

So what jottings could I take with me without taking a “trunk story”? The info packet suggested we bring “images, titles, notes” (something like that). After much unnecessary consternation, I decided a few rough paragraphs counted as “notes.”  I needed a security blanket, and I made one out of words — about 1000 of them, not many of which went into my final Clarion West word count, which was something like 25,000.

I needed a security blanket, and I made one out of words — about 1000 of them, not many of which went into my final Clarion West word count, which was something like 25,000.

I made a wise decision (for me) before I left. In the “advice from former students” section of the packet, some blessed soul said (something like) “Don’t feel pressured to do the six-stories-in-six-weeks thing if it’s not for you.” I knew I couldn’t write a coherent short story in a week (at that stage in my life), so I didn’t. Not counting Paul Park’s exercises, I wrote a total of three stories, each spaced out by two weeks. And by the time the workshop was through, each instructor had read at least one of my works. My plan worked out fine. Future Clarionites, feel free to follow it if it serves ye well.

With my writing worries sorted out, I then packed a bajillion suitcases with the help of my now-girlfriend, and blasted off to the space station.

This post is the first in a series of ten about my experiences at Clarion West Writers Workshop in 2008. Clarion West is an intense six-week writers’ workshop held at...

Twitter:

Twitter:

Join the conversation