As you might have heard, I’m working as a clinical schoolteacher — basically, doing three months of unpaid student-teaching en route to earning my full teaching certificate — as mentioned in an earlier post. The gig’s at an elementary school in the Fort Worth Independent School District, in an economically disadvantaged neighborhood. Many of these children, for instance, go home and spend hours and hours alone while their parent(s) work multiple jobs, and the children often lack proper clothing or supplies such as glasses.

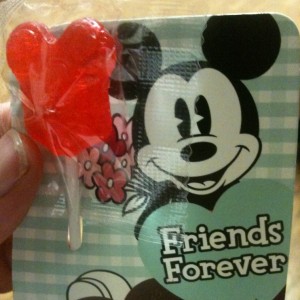

But one student still thought to get me, in addition to my coordinating teacher, a Valentine’s present:

My observations so far largely fit with what I’ve observed as a substitute teacher, a role in which I often substituted for an aide, and for the same teacher across several days. So, as a substitute I did watch regular teachers teach.

They’re mean to students. Often.

According to the fantastic instruction FWISD’s Substitute Academy gave me on behavior management (I call it “crowd control”) — and this jives with my personal experience — administering sarcasm destroys your credibility and your relationships with students more than anything else. Sarcasm’s really nothing more than a way for teachers to vent their frustration and scare students — a losing strategy, in the long run, since students lose much of their respect for downright mean teachers and don’t learn as well. There’s no need to be a Tiger Mother.

For example, teachers will yell at students for not following worksheet directions, when it’s clear the students often don’t understand the directions because, say, they can’t read them without glasses, or they’re interpreting the unfamiliar words in a novel way, or the terrible textbooks’ directions are ambiguous in the first place. And this anger when they come to the teachers asking for help with the directions!

Of course, in disciplining children, there’s no reason to coddle and give ribbons for every good deed, either. But there’s nothing wrong with treating children with kindness, telling them thank you, praising them for succeeding at what is actually difficult for them — following directions, focusing, getting an answer correct, and so on. Telling a student “Good” never killed anyone, and an encouraging, welcoming classroom community helps students learn; yet, so often I hear teachers mock students and then support their offensive behavior with a chest-pounding, macho, “toughness” credo. Yeah right. Maybe you’re just a jerk, or maybe you just don’t know what you’re doing.

Way over on the other hand, though, it sure is easy for me to spend a week or two in a new community — the school — and pass judgment, especially when I’m not under the strain regular teachers are. (Teaching to the high-stakes tests, for instance.) Kind of like committing a cross-cultural drive-by. And, I don’t want these schoolteaching blog posts to turn into passive-aggressive attacks on my co-workers, you know? But I’m calling it as I see it, and when the time seems appropriate, I’ll mention my concerns to my superiors. I do defer to their chain of command, perhaps too frequently; but, when you’re the low man on the totem pole, brazenly passing judgment isn’t always the best thing to do — especially when my superiors have years of experience that might inform their actions in ways I don’t understand yet.

Of course I don’t really believe any of that… Though I do believe this: in assessing the public school system, you can’t point fingers at any one problem (especially just because it might be politically popular to rag on that problem). The errors are system-wide; everything from underfed, hungry students to funding problems to malevolent teachers to absent parents to … You can’t single out any one thing, and you can’t ignore the good work that’s being done, either.

But I’m furious at the way teachers write off students’ misbehavior (or just problematic behavior) as due to some sort of intrinsic “badness” of the children that the teachers act like they’re incapable of addressing. I’m not really furious at the teachers, but at a culture-wide reluctance to adopt a philosophy such as Pragmatism, where one doesn’t opine about metaphysical ethical essences, but just takes the most practical assumption. Assuming at-risk students are intrinsically bad might be practical if you don’t want to stick your neck out, or if you don’t want to make the extra effort, but it’s not practical if you want to help people. And children are people. After all, adults are often just as immature as they are.

And what about gathering the courage to ditch the paint-by-numbers worksheets and make your own material, material that’d be relevant to the students and help them understand and care about their work? In class we read this long story about settlers’ candle-making. These children have no idea what the “mold” is that settlers used to create candles. There were too many paragraphs for the story also. Why not write two or three paragraphs about the snow days, answering some questions you overheard the students ask about the weather? When it’s not busywork, and when the material is relevant to the students’ lives, discipline problems often disappear.

21st Century Schoolteaching (via Our Man in Tirana)

As to that student who needs glasses (see earlier post). Some questioning, and my own experience, indicates the delay in getting glasses to students is a persistent and district-wide problem. If my questioning about the glasses supply chain turned up correct answers, a corporation called Essilor is the contractor responsible for getting glasses to students, as the students are entitled to receive under various federal legislation (if I recall correctly). The contractor apparently operates under a (state? federal?) grant, which means they have an obligation to do their work (i.e. it’s not charity), and that grant might specify a timeline for delivering the glasses. Also, the grant should be publicly available; via Twitter or email, I’ll ask organizations such as ProPublica how to track down the grants, and if I have to, I’ll file an entire FOIA.

Don’t mess with my students.

Twitter:

Twitter:

Join the conversation