Note: In 2021 I’ll publish at least one blog post per week. Here’s entry 11 of 52.

I used to not believe in trauma anniversaries, the distress a person can experience when a calendar date lines up with a past violation of their well-being. To my perspective back then, steeped unawares in the default corporate values, trauma anniversaries seemed too fantastical: how could a person’s nervous system remember all that, and how could it be tipped off that the fateful date was approaching? More importantly, multiple well-paid psychiatrists for decades, their corner offices fancy with diplomas and oak desks, never mentioned trauma anniversaries to me a single time, and consistently portrayed the mania I sometimes experienced as a meaningless, causeless brain fart. But during every April and May for seven straight years, indeed usually on the very date of May 31, I’d experience severe, hospitalizing mania. Despite the timing being as dependable as the Old Faithful geyser, the psychiatrists displayed zero curiosity about it, whereas friends would sometimes ask natural questions (“Why do you think it happens then?”). Unanimously, the psychiatrists told me (not so forthrightly of course): Just take these tranquilizers (“medicine”), these dopamine antagonists, pay up, and you might be able to have some sort of meager life over there in the corner, if you’re lucky. They didn’t say, while the psych pills shrink brains and tardive dyskensia looms at your door.

It wasn’t fun. The stigma has been perhaps worse than the mania. I’ll give two examples of hundreds. In 2000-2001, I attended the University of Dallas on a full scholarship to study philosophy and classics (Latin and ancient Greek). It was a small Catholic school, and I was an atheist fish in the wrong, small pond. U.D., as it was called for short, made it a selling point of their school that students would all take a trip to Rome together sophomore year, and I was really excited about it. After mania prevented me from participating in classes for roughly three weeks — this was two decades ago, before psychiatric diagnoses were so common that universities created more explicit policies for mental health emergencies — U.D. informed me I wasn’t going to Rome with everyone else. (Not long after, I dropped out.) Their decision made some sense: what the hell would you do practically with a student suffering manic psychosis, in the hotel, in the airport, etc.? In some cases, it makes sense to give a manic person a tiny bit of benzodiazepine, to help them sleep, and once they wake up, everyone together figure out what’s going on using a process like Open Dialogue; but, colleges weren’t and aren’t prepared to intervene that substantially (although you can imagine it someday, what with K-12s employing special staff to attend to some students’ medical needs, and now campuses outfitting themselves for the horrible idea of in-person classes during coronavirus). Undergraduates in their twenties, with private school backgrounds, haven’t lately been expected to be adults capable of handling themselves. The whole setup was paternalistic to begin with: the U.D. authorities were to watch out for our well-being in these scary foreign lands filled with terrorists or whatever. Bottom line, they looked at me and said No. Just as my K-12 considered kicking me out for the same reason (manic episodes), in a dramatic meeting with my family. The unfortunate “help” I was given for the whole dilemma, the answer from Texas in general was, go to psychiatrists, who will say there are no causes you can do anything about, and take your piece off our game board, get out of everyone else’s way. A very few years later, one of my best friends was going to Japan to teach English (and then went to India for six months); I was going in and out of psych hospitals. It was really discouraging, and I routinely used an imaginative, puffed-up, hypomanic grandiosity to sustain myself, to not think about (to dissociate from) my problems and keep writing music/words and pursuing all my other interests in rude opposition to “having a good work ethic” since I didn’t want to go along with seemingly everyone else’s philosophy of Don’t think too hard, don’t care too much, get a job any job.

Example number two. Here in Seattle, I went to a party for Clarion West Writers Workshop (which I completed in 2008), sometime between 2016 and 2019, honoring an author whose name I can’t remember (she was writing fiction about presidential assassinations, if anyone recalls…to be clear, that is people assassinating presidents, not presidents assassinating people). A random party guest was an employee at Navos, a greater Seattle mental health clinic, as a therapist or some related occupation. I happened to be standing in the small group to whom she was talking, merely happenstance party conversation, people holding drinks and the like. She asked if anyone was familiar with her workplace, this entity called Navos. I said yes. She blinked and said, “Wait, you volunteer there?” And I said, “No, as a patient.” She then literally raised up her nose in disgust and turned away from me. The other surrounding partygoers followed suit, showing disgust and turning away from me also. The look of disgust is a common expression made at someone slotted into a negative image role. Before the pandemic, once patients were called up the stairs from the waiting room at brick-and-mortar Navos, where the security guard watches them from his desk, the therapists would use key cards to let them through locked doors, under the rarely correct assumption that these medicalized humans might act out dangerously. It felt like being a zoo animal. A zoo animal in the social services, mind-twisting, smiley face version of a prison.

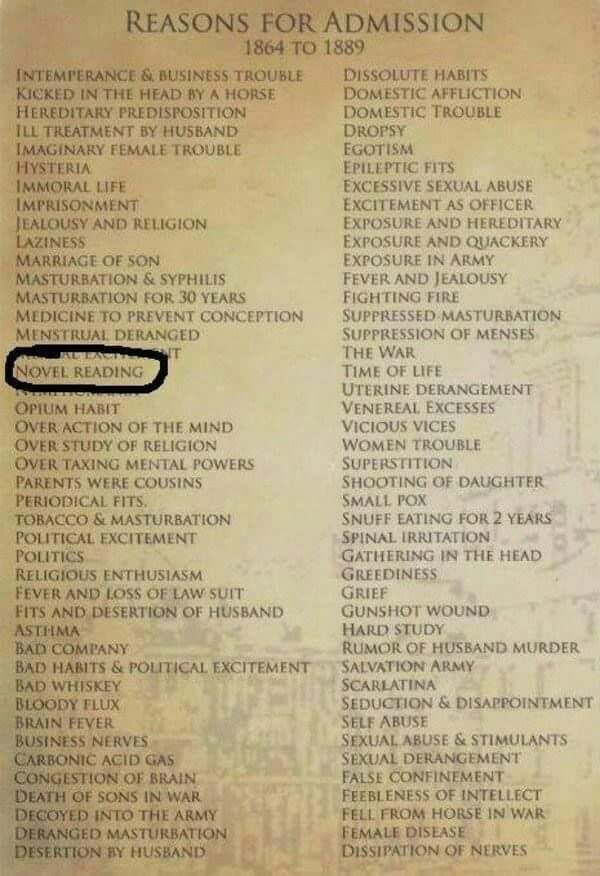

It’s taken several years, but I’ve made a deep study of the extensive decades of literature disputing the genetic theory of manic-depression, how the twin studies are used, the chemical imbalance theory, and other falsehoods, plus participating in a Hearing Voices Network chapter and devouring multiple books, podcasts, and documentaries detailing the success stories of psychiatric survivors (the secret that people have made full recoveries from repeated bouts of psychosis and tapered off their drugs is slowly becoming more widely known). I’m still studying this material and related helpful information, much of it published in peer-reviewed scientific journals, not that practicing psychiatrists read those (they’re busy going on ski trips with the money, possibly bringing their manipulated patients along for sex, too). But for those who might be unfamiliar with this vast literature, let’s just take the chemical imbalance theory briefly, a widely advertised theory which lately mainstream psychiatrists have had to start backpedaling. Millions upon millions of people in the United States today swallow psychopharmaceuticals daily, often antidepressants or sleeping pills; taking “meds” for the psych diagnoses considered less severe has become ordinary, a recommended way to survive the impossibilities of paid-work, while those with the harsher labels (schizophrenia, psychosis, etc.) are considered an abnormal, bad underclass. These millions and millions of people, whether with the “normal” labels of depression etc. or the more severe ones, are commonly told they “have” chemical imbalances. Which I suppose is like “having” a pet rock, only it’s invisible. The mystique of the doctor in the white coat can take over, preventing patients from asking obvious questions. How often do we hear, in place of evidence and logic, about a doctor, politician, or other idealized figure: I trust him; he’s a good guy? Yet we don’t need to feel an affinity with a prescriber; we need to ask the prescriber questions obvious to an impartial observer and verify what’s going on. Which chemical is imbalanced? How much of that chemical per microliter is too much? How much of that chemical per microliter is too little? What’s the safe range, per microliter, for that chemical, whichever one it might be? Who invented the chemical imbalance theory? When was it invented? Was it initially published in a scientific journal, and if so, what’s the citation for that article (and obtain a copy)? These very basic who what when where why and how questions are too often not asked, among other reasons because patients sometimes outright fear their doctors, their legal powers, and their way of snapping back at questions they dislike. The patients’ brains are being dramatically altered without enough questioning from the patients, as if psychopharmaceutical treatment is simply taking clocks to repair shops, to use sociologist Erving Goffman’s analogy in his 1961 book Asylums. With no time or motivation for curiosity, customers taking broken clocks to repair shops do not ask the repair-workers, Who invented clocks? Why do clocks need springs? The customers simply expect the gadgets to be fixed, then they pay the fee and bring the clocks home. People treat their own brains just like that. The error is supposed to be from birth — but sorry, there are no blood tests to prove it (no answers to the microliters questions), and all the vaunted genetics has persisted at a research level for a very long time, scrutinizing without holism people crammed into pidgeonholes, nothing definitive found — and you are to take the pills to remediate your inherent wrongness and then get back to the miserable paid-work for evil corporations and their ancillaries. Mental health suffering is increasing, understandably because humanity, in big picture terms, is seconds from self-caused extinction; watching humanity kill itself and many other species, psychiatrists do not have much to offer for explanation or success stories, but their industry does have criminal convictions at Nuremberg for enabling genocide, and see also the American Psychological Association’s more recent participation in CIA torture. Trusting these people to make dramatic alterations to your brain without asking questions isn’t a good idea. It isn’t mental health.

The chemical imbalance theory came about because scientists began noticing that when people were given certain pharmaceuticals for unrelated physical conditions, they would also act in different ways, so if it was considered good for them to act in those new ways, then they must, the scientists thought, lack enough of that chemical supplied by the pharmaceutical, and therefore they need to swallow some of it regularly to act right. In other words, if you aren’t doing such-and-such, but this other thing makes you do such-and-such when you swallow it, you must have a deficiency of that other thing. This is very bad reasoning. It’s like saying, imagine a shy person. The shy person is at a bar, they’re nervous about their clothes and hair, and they don’t know what to say to the other patrons, to the bartender, etc. But when at the bar we give them alcohol, they suddenly start talking more! Therefore they must need alcohol supplementation, a bit of booze each day, to correct their alcohol imbalance and act with the proper gregariousness. This specious reasoning — X makes you do Y so not doing Y must be caused by a lack of X — fits multiple types of causal logical fallacies. Imagine a psychiatrist in a critical reasoning class! You’re not lying on the floor currently, however when I punch you in the face, you fall to the ground; so, if you need to lie down, the obvious solution to your postural imbalance is to have me regularly punch you in the face a little bit each day for ongoing maintenance against your being-punched deficiency!

The trauma anniversary I was experiencing was combined with dissociation. Dissociation is tuning out in the face of overwhelming emotion. For instance, families in hospital rooms of a dying family member will too often largely, or almost completely, ignore the dying person, and stare at their phones to distract themselves and prevent themselves from experiencing the intense emotions and meanings regarding the impending death. After all, why say goodbye to grandpa when you can scroll instead? Anyway, I did many things to help overcome dissociation to some extent, mainly noticing when I was doing it and then slowly testing out feeling and expressing the emotions instead, which by the way, has physical analogues: feeling and expressing emotion isn’t just rearranging your internal world (like most of psychoanalysis is), but action-y, doing things outwardly, like cursing and kicking a trash can across the room if you’re really, really upset. This took me several years to get comfortable with; I still have a lot more to go. Further, the mania was dissociative in itself: escaping from overwhelm into delusional, grandiose fantasy. Sometimes it seems many people do not even know when they’re overwhelmed, since psychological education is insufficient or nonexistent, not to mention people understandably have blocks against considering what these terrifying topics mean for them. Even though for years and years, April and May meant mania for me, especially May 31, the calendar date of May 31 would roll around and I wouldn’t even know it was May 31. You would think, this most consequential date in my life, that sent me to in-patient lock-up over and over, would register on my radar as it neared. But it was too overwhelming, so I by habit didn’t even realize when it was coming. Among PTSD there are two types (I didn’t learn this from any psychiatrist): the popularly known one where you can’t stop thinking about the trauma, and the other type there’s less awareness about, mine, where you don’t think about the trauma at all. Not being able to find what was causing the trauma anniversary was as habitual as putting one foot in front of the other while walking: something I later was able to focus on starting a little at a time (baby steps), but for decades was more comfortable just going about on the autopilot approach, not thinking about it. Even if I tried to think about it, I could never pin down any specific trauma that happened to me during any long-ago April or May. My mind wouldn’t surface images or facts about any long-ago events in connection with the April/May period. Plus, it somehow didn’t seem “scientific” that something might have happened during those months in my past, a specific example of corporate propaganda (corporate portrayals of science) obscuring a person’s life from him. To top it all off, psychiatrists repeatedly found nothing about any of this worth talking about, same as the instance when an orderly physically assaulted me in a hospital, knocking me to the floor violently just for making a sarcastic comment, and multiple psychiatrists (attending and out-patient alike) said not a damn thing when I mentioned it. In fact, they used what educators call extinguishing. This is the classroom management technique where you ignore a student’s minor misbehavior, not reinforcing it, hoping it’ll disappear on its own, as it usually does (if indeed it is misbehavior; why should students be compelled to sit in cramped desks all day and penalized for “misbehavior” if they refuse?). Whenever I brought these reasonable topics up to psychiatrists, they used extinguishing. They’d just be silent. And then they’d change the subject to something comfortably medical in vibe, like dosages or the side/adverse effect of hives I got from neuroleptic. The psychiatrists felt far more comfortable talking about little checkbox algorithms for physical symptoms. Like eliminative materialists in academic philosophy departments insisting that minds don’t even exist, the psychiatrists kept diligently away from topics such as dissociation, which are actually decently understood by trauma experts. But again, practicing clinicians don’t read that material; that’s why they bully you instead if you ask too many questions, a trick they probably pick up from grand rounds questioning in medical school among other sources. In Fort Worth around 2002 or so, I once saw an orthopod with a sign in his waiting room that said something to the effect of, Any material patients talk about from the Internet will be ignored. Before the widespread adoption of the Internet and especially social media, medical professionals could easily tell each other at conferences how much their patients loved them (perhaps mistaking fear for respect or love), but now I think they’re slowly seeing the pitchforks approaching their insular world. Though some of them still talk blithely on youtube’d recordings of their conventions, making fun of their patients (accustomed to what they are doing, the psychiatrists might consider it merely analyzing their patients for their colleagues’ benefit), maybe unaware that those outside their myopic cult hear them and disagree. If you show your psychiatrist recent articles like this one from earlier this year — “What I have learnt from helping thousands of people taper off antidepressants & other psychotropic medications” by Adele Framer/Altostrata, the founder of SurvivingAntidepressants.org, published in the peer-reviewed Therapeutic Advances in Psychopharmacology journal — it’s not like the psychiatrist is going to say Thank you, and I think we all know that. Maybe it’s time for people to stop identifying so dogmatically with psychiatric labels (voted into existence by psychiatrists at conferences) and obsessing over the band-aid commodities sold for those labels (marketing categories), as if it’s the patients’ fault rather than corporations’ for wage-slavery, widespread pollution, and the rest.

Trying to figure this stuff out, I went to a Seattle psychologist who was very knowledgeable about alternative views, and understood that emotional distress is a human problem, not a chemistry set or test tube problem. I gained some very good information from him, although I wasn’t really ready for it until later in my life. One thing he did with me was called brainspotting, an offshoot of EMDR (Eye Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing). I’ve heard the psychologist Daniel Mackler (different person) describe EMDR as a way to helpfully shortcut someone toward discovering what might be causing a traumatic reaction, though not something that heals the psychic injury on its own. A discovery tool, not the cure. So this other, Seattle psychologist pointed a red light at my eyes in accordance with the brainspotting procedure. It caused me to blurt out a single word. I won’t specify it here for the privacy of myself and others, but it was a proper noun, let’s call it R. A few years went by before I recognized the significance of it.

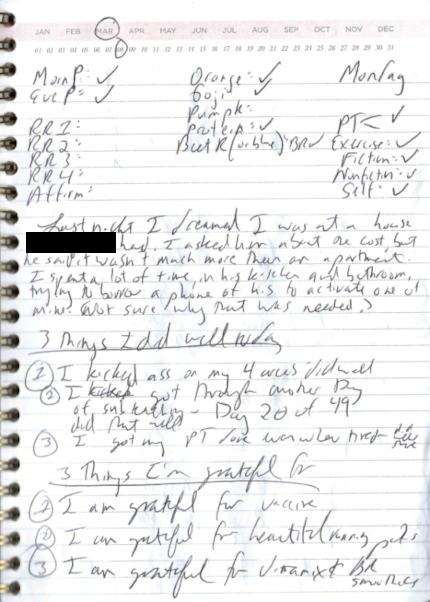

In the meantime, I decided the best way to engage with this mysterious trauma anniversary was to always know the calendar date, so I’d be prepared to use grounding techniques and anything else I needed when April, May, or May 31 arrived. I found a very helpful type of journal, pictured above left and at the start of this post, that lets you circle the date and month. That physical action (as opposed to, say, the endless musings of psychoanalysis) of finding the month and the day on the horizontal lists and circling them helps me always know the current calendar date. Before the logbook, when I was picking out a box of fresh spinach at the grocery, I’d have to check its expiration date against the date on my wristwatch. But now I always know the date and no longer need to do that. Whereas previously, the April/May, and/or May 31, time period would stay in my subconscious, below awareness, too scary to be confronted, I was now bringing this feared problem into my awareness every single day, and I still do this daily. (Makes me think of Jung’s shadow concept or Le Guin’s novel A Wizard of Earthsea.)

I also use the logbook for other purposes too, most importantly to center my life on my calling of writing, which I’ll get to in a moment. I use the logbook to record my dreams each morning, if I remember them, and each night I use it for two exercises psychologist Terry Lynch recommends (his psychology courses are the most helpful material, bar none, that I’ve come across for understanding mental health issues). The exercises are writing down three things I did well that day and three things I’m grateful for from that day. The did-well exercise definitely makes me less susceptible to angry thoughts about how I’m supposedly no good at anything and the like; the exercise encourages me to have my own back, to defend myself from occasional automatic thoughts that are really internalized oppressions, not truths. The gratitude exercise makes me more optimistic in general. However, the benefit from both exercises has started to wear off somewhat, because over time I’ve reached the point that, seeking to go to bed quickly, I just scribble down the six things quickly like rushing through a crap homework assignment. I’ve started reading the six things aloud to combat the unthinking, rushed behavior. Finally, I use the logbook to check off certain foods I try to eat each day for nutritional purposes (a large navel orange for myo-inositol, pumpkin seeds for zinc, and so on), plus certain tasks, a.k.a. areas, I attempt to work on daily: writing fiction (it’s set in 2036), nonfiction (a book about hacktivism), and self (journaling and reading psychology stuff or books that teach practical skills). In years past, when I tried to keep a record of what I was up to, I’d give up after a day or three. But now I’ve been using the logbook consistently for months and months (and I always know the date!).

Two principles have helped me stay consistent with using the logbook daily. One I call “focusing.” I looked at myself and thought, what do I really want to focus on with my life? Do I really, truly want to be investing free time in playing Dungeons & Dragons with online friends, or rehearsing Spanish vocabulary flashcards? Those would be nice to do, but I’m actually here to accomplish various specific writing work. Thus I made a powerful commitment to spend my time actually doing that, not distracting myself with secondary goals that might be nice someday (such as more Spanish skill). Implementing that helps with mental health, too, because I’m not hiding from the challenges of writing by doing something I deep down know is less important to me. I vigilantly circumscribe who I spend (very limited) time with, because all sorts of friends and frenemies habitually criticize me and how I spend my time, or tease me at length as to why I should be playing Dungeons & Dragons with them or coming to this or that offline event, maybe because what kind of weirdo writes longform blog posts anyway, who does that? But I have to protect my availability, especially since writing is exceptionally time-consuming work, particularly when I prefer a thorough and research-intensive style. Second, I jettisoned the idea of deadlines or pressuring myself to write however many words daily. Instead of trying to fit those perfectionist demands, I decided to follow my own curiosity and work on the projects however that curiosity leads me. I still task myself with, besides my day job, spending at least an hour a day on three writing areas — fiction, nonfiction, self — plus doing some form of exercise, so four or five hours total, but since all that is frequently not possible every day (yet), I came up with a simple solution, a way to look at the situation with compassionate objectivity (to borrow Hillary Rettig’s phrase). My real task every day is just to to write on different lines in my logbook Exercise: Fiction: Nonfiction: Self: in case I complete any of the areas and can check it off. That simple chore, which takes perhaps 15 seconds, means that I’m still focusing on these three/four primary areas of work. I’m still caring about and trying to do them, even if it’s just writing down those four words in my logbook. If I don’t work on, say, fiction some particular day, well, life is life, just do the best you can. So I jettisoned all the crazy stress about deadlines and words-per-day, which really came from other people’s expectations, like a lady who once randomly lectured me for not writing as fast at a writing workshop as she thought I should, even though she wasn’t even part of the writing workshop! (She was there hunting for business intelligence for her company, I think.) When you really look for it, and aim to stick up for yourselves and others consistently, you realize there are many people circling around the world, prodding for weaknesses that they can mock you for if you’re vulnerable like a sitting duck, not skilled with firing back counter-insults or leaving the situation. I’ve learned to try not to ask others for their thoughts on these provocative topics too much offline, because bringing up a trouble or curiosity or passion I have all too often gives them an opening to mock or assert superiority without providing any sort of expertise to justify it. So over hanging out, I much prefer writing down the four areas in my logbook, working on them if I can (longhand feels so much more connected and channeling than typing!), and then checking them off one by one. If you’re thinking about trying this logbook technique, it might help to recall that you don’t have to do it the exact same way as I do. Over time, you can learn to trust yourself and your judgement, if you don’t already (many people with mental health problems don’t, though they might not admit it, not even to themselves, like political radicals asking their psychiatrists for permission, or oh excuse me, if the psychiatrist would think it’d be a good idea, before becoming a water protector or the like). You can vary the logbook as you see fit.

Back to the trauma anniversary and R. The idea for the self area — for journaling every day for some 30-90 minutes — came largely from Daniel Mackler’s thought-provoking youtube videos and Terry Lynch’s amazing book Selfhood. I won’t here describe how precisely I do my journaling, as that’s enough to fill a whole separate blog post. The point is, when I first purchased my blue journal (pictured below to end this blog entry), I immediately had the thought come to mind that I should use the journal to write about R. A powerful felt sense told me that doing so was going to be extremely helpful, and I no longer needed anyone else to confirm this for me or debate it. As Lynch says in this hour-long video on recovery from bipolar disorder (where he also mentions how important it is to take baby steps out of comfort zones; and, how important it is for people with manic-depressive tendencies to notice when, in a precursor to psychosis/delusion, they start using grandiose fantasy, such as daydreams of being a superhero, as a coping strategy for avoidance anxiety / putting off addressing problems), when people have severe mental health diagnoses, a crucial piece of their trauma history might not be the big trauma everyone’s looking for, the really obvious horrible thing that happened to them that everybody knows about and talks about. It could be some event that seems small in comparison, or even mundane from a very macroscopic perspective, something that commonly occurs in most people’s lives. But that “small” traumatic event could still be very meaningful yet unresolved for the particular person; usually, it’s events in childhood or adolescence, through which later life can be filtered. That’s how it was for me with R. Over the next several months, working diligently and just about daily, I filled up the entire blue journal with my thoughts and feelings and notes, almost completely about R, sometimes using investigative journalism techniques, researching public records and maps and so on to ensure accuracy (it needs to be a story with personal meaning, but also a story with factual currency in the social world).

Guess what I discovered! The boiling point of the R situation happened in April 1997, and just days later, I exhibited strange emotional distress, something I’d never done before. (I obsessed over packing and unpacking a bookbag and couldn’t respond in conversation with my family, as if I couldn’t even hear them, when they were asking me from across the bedroom what was wrong.) I was that exact month sent for the very first time to a mental health provider. Putting together these pieces wouldn’t be challenging for an impartial, outside observer with skill; in fact, they could probably do it in just a few minutes if presented with enough raw material about a client. But because I had/have the form of PTSD where I tended not to think in any detail about the trauma (except perhaps to haughtily dismiss its relevance), and because psychiatry was of no help (and in fact, with their extinguishing and their dodging subjects like dissociation and abuse by orderlies, psychiatry made matters worse), solving this has taken me decades. It’s no longer difficult for me to acknowledge that people remember, even if only subconsciously or somatically, what happened to them long ago (see savants’ feats of memory for instance, or the fascinating book The Woman Who Can’t Forget by Jill Price), and that something like glancing at the clock at the corner of a laptop screen might inform the subconscious that the date is May 31, even while the conscious mind is running madly away from the trauma anniversary. There’s actually another trauma anniversary for me in August, of lesser strength; on August 24th, 1998 came my second incident of psychosis. It was August 24th 1998 that got me put on psychopharmaceuticals. Second only to the April and May months, August has statistically been the next most common time period for the mania episodes. Tomorrow I’ll start filling up my new, second journal about that August trauma anniversary, and that August 24th 1998 event, whatever it was: I currently and for the last decades have had only a single image of it accessible in my memory. So I’ll have to piece it together, with investigative journalism-type research, looking at archived computer files, finding old school yearbooks in libraries, and so on, as well as by describing and narrating that one single accessible memory-image in such immense detail that additional memories begin surfacing. I’m glad I filled up the blue journal about R; now I no longer fear the April and May time frame, and indeed, I’ve made it through April and May unscathed recently, with the seven year nightmare stretch receding into the past.

Rather than psychosis, we should actually say extreme emotional distress. Whereas the word “psychosis” makes a person seem different, nonhuman, a deserving target of stigma and shunning, extreme emotional distress can happen to anyone, and it does. The handwaving about genetics and chemical imbalances, from which no conclusive evidence or tests have ever been provided, papers over the reality that millions upon millions of people are diagnosed with psychiatric labels and put on mind-altering brain-shrinking drugs, some of which already went into shortage during the pandemic and might go into shortage again (there will come a day when these pills are no longer readily available in this or that region, and patients are left to dangerously cold turkey off them), that elders are being force-drugged with neuroleptic in nursing homes (to make them easier for staff to manage), and that any calamity, from another coup attempt in the United States to a hurricane or an earthquake to the loss of a beloved pet, can be the last straw that causes your mind to snap if you don’t know how to address the psychic violation, and sometimes even if you do. You’re not immune from humanity, and along with so many other psychiatrized people, I am not excluded from it, try as some might.

I hope this post helps someone else suffering from trauma anniversaries and/or the PTSD where you don’t or can’t think about, where you dissociate from, can’t even remember, the specifics of the trauma.

This blog post, How I addressed a trauma anniversary that psychiatrists weren’t curious about, by Douglas Lucas, is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License (human-readable summary of license). The license is based on a work at this URL: https://douglaslucas.com/blog/2021/03/20/trauma-anniversary-curiosity/. You can view the full license (the legal code aka the legalese) here. For learning more about Creative Commons, I suggest this article and the Creative Commons Frequently Asked Questions. Seeking permissions beyond the scope of this license, or want to correspond with me about this post one on one? Please email me: dal@riseup.net

Twitter:

Twitter:

Join the conversation