In January I attended a Law and the Media seminar in Houston that focused on WikiLeaks. The Houston Bar Association, the Society of Professional Journalists, and the Houston Press Club sponsored this 26th annual Law and the Media event. I wrote “Julian Assange Prepares His Next Move” for Salon.com using material from the seminar, but I also took photos, detailed notes, and a pretty good transcript, items which I’ll reproduce in part with this blog post.

(Big thanks to my friend Kristyn for hosting me at her apartment.)

Just a little more than a hundred people attended the seminar. This was the agenda:

-

8:00-8:55: Registration and Continental Breakfast

-

8:55-9:00: Welcome and Introductions

-

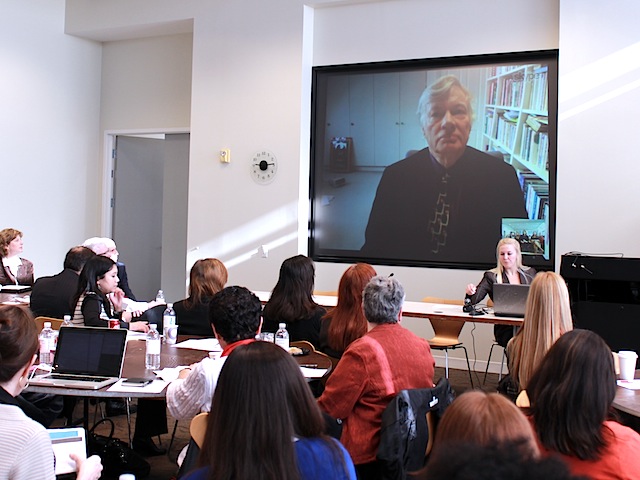

9:00-10:00: Inside the WikiLeaks Legal Team: Geoffrey Robertson, QC, Doughty Street Chambers, via Skype from London

-

10:00–10:15: Break

-

10:15-11:15: WikiLeaks and America’s Campaign Against Al-Qaeda: Eric Schmitt, New York Times

-

11:15-11:30: Break

-

11:30-12:30: The WikiLeaks Debate: Panelists: Lucy Dalglish [Reporters Committee for Freedom of the Press, Executive Director], Don DeGabrielle [private international governmental investigations attorney, former U.S. Attorney, and former FBI Special Agent], David Adler [federal criminal defense attorney and former CIA officer] and Tom Forestier [Moderator; law firm managing shareholder].

Transcript of most of the seminar below. Quotations indicate exact speech. Brackets indicate my clarifications. Brackets with my “– DAL” signature indicate my comments. Everything else is paraphrase. Mistakes mine. This transcript assumes you have some familiarity with the material.

Geoffrey Robertson

Robertson began with three quotes: James Madison on the importance of a free press for governing knowledgeably, Theodore Roosevelt “calling on muckrackers to destroy what he called ‘the invisible government,'” and a Supreme Court opinion in New York Times Co. v. United States saying the only protection for the public lies in an enlightened citizenry. “Assange takes this philosophy seriously.”

Assange uses electronic methods to keep sources anonymous. “You could waterboard him for weeks, and he couldn’t name his source, because he wouldn’t know.”

WikiLeaks published exposes on “the malpractice of the church of Scientology” and “tax evasion in the Cayman Islands” and “banking fraud in Iceland”; “all these releases were of obvious media interest. Assange is often seen as being left-wing, but WikiLeaks published the so-called Climategate” wherein “Essex University seemed to be rigging the data.”

“In quick succession in 2010” WikiLeaks published “the material that is alleged to be posted by Bradley Manning. There was Collateral Murder, which was manslaughter. An extraordinary revelation. I thought it should have been called Collateral Manslaughter because it was a tape that showed the killing of two Reuters reporters, children, and several civilians.” It was “a war crime.”

Skype call interrupted by a Windows automatic update on the Texas side. Call resumed.

“Iraq-gate included 400,000 raw field reports that showed many thousand more civilian causalities than had been estimated. A treasure trove for future historians writing about that war, showing exactly how it was fought on the ground.”

“Obvious stories of public interest.” A “very interesting fact: in 2010, as these revelations were coming out, a number of countries were so disturbed by what WikiLeaks was doing that they dropped all WikiLeaks-related websites and threatened to jail any of their citizens who were caught sending material to WikiLeaks. Which countries were these? […] China, Syria, Russia, North Korea, Russia, Thailand, Zimbabe.”

“It was with Cablegate in 2010 that we did get a burst of hysteria from the United States. It was the release of diplomatic cables […] published jointly by the New York Times, the Guardian, and Der Spiegel, with fact-checking, removal of names, and so on done together by all the organizations. Criticism from the government came not against the New York Times but singled out Assange,” casting him as “this peripatetic Australian with this supernatural power.”

When there was criticism of Rupert Murdoch’s News Corp invading privacy with cell phone hacks there was “no real protest about” Murdoch from governments.

Vice President “Joe Biden accused” Assange “of being a hi-tech terrorist; “Huckabee called for his assassination”; Sarah Palin said “he should be hunted down like bin Laden.”

When going to visit Assange in Norfolk, Robertson keeps “an eye out for Navy SEALs.”

Robertson has received “death threats from middle America by email.”

Robert Gates, former Secretary of Defense, said Cablegate resulted in “no long-term damage.”

The pragmatic United States diplomats were “so insightful that when all this was published, President Clinton suggested Assange was a secret CIA agent.”

“America was upset; its pride was wounded by this pesky Australian. It couldn’t — I guess because of the First Amendment and Democratic Party politics — attack the New York Times.” The attack on WikiLeaks is “a betrayal of the founding fathers who claimed belief in freedom.”

People keep saying “Assange has blood on his hands”; “let’s examine this”: “2.5 years and not a single causalty.” So “that’s the first point. No blood on WikiLeaks’ hands. Those who said there was were talking nonsense. We wouldn’t expect there to be casualties because these cables were not classified Top Secret” as the “Pentagon Papers” were. “Top Secret is a classification where there are likely reprisals from publication.” [Reviewing US government information on classification levels, I found nothing to support this claim. — DAL] “So obviously” the writers of “these cables didn’t expect reprisals.” That “two and a half million people had access to these particular cables” makes it “so entirely false to suggest lives would be at stake.”

“It’s the responsibility of a government that puts sources at risk to guard them; to encrypt their names, [to encrypt] cables, [and] to have a proper classification policy.”

It comes back to the Pentagon Papers and the principle that “the duty of government is to protect its sources.”

“Proper classification should” adhere to “four principles”: “Firstly, citizens have a right to know what the government does in their name”; “Secondly,” a “government has the responsibility to protect” sources”; “Thirdly, outsiders who have obtained it [classified information] should not be punished unless they got it by fraud” or “bribery”; and fourth, classification “should not stop whistleblowers from” revealing “war crimes.”

“It is not clear what communication there has been between Manning and Assange.”

“Look at the Espionage Act.” There are “three positions between journalists and sources. First is that the journalist receives the information unknowingly such as through the traditional brown paper envelope or through the Internet in various ways. It seems in that situation no one would suggest the publisher should be liable […] If it’s in the public interest, there should be no criticism in publishing [it].” 2. Intermediaries. With an “intermediary there is contact. The source says ‘I’ve got information of importance, how can I get it to you?’ […] The journalist says ‘drop it in a certain place at midnight’ […] arranging to receive information […] should not be criminal.” 3. “Where the journalist contacts the source and persuades him or her to breach confidentiality of government or bribes him, then that is soliciting and that should fall under the scope of the Espionage Act.”

Electronic leaks are “here to stay.” The “Wall Street Journal has something called Safe House that guarantees safety of information, if you trust Rupert Murdoch.” And there are “other sites outside the constraints of traditional publishers. So we’ve got to accept — governments and corporations have got to accept — that confidentiality is going to be limited where it deals with information of public interest. Information will not only leak; it will go viral on the Net. You remember, perhaps, that YouTube film set in Domino’s Pizza; a secret camera depicted photographs of one of the Domino’s Pizza cooks stuffing the pizza in his nose before” finishing with it, and “Domino’s stock went down 10%.”

“Corporations have to face up to the fact that this is the new power of ordinary people. Ordinary people — that [wrongly] condescending phrase.” We must “remember that WikiLeaks stands there […] at a time when Google is blocked by 25 countries in the world. You can’t get YouTube in Turkey.” Now there are “two billion people” connected online. “For better or worse, this prospect of breaches in confidentiality is here to stay.”

With “unredacted” material published “directly on to the Net there will be more danger, but perhaps more benefit. We must live with this” and “we should welcome” it.

“Some analysts say” that “the Arab Spring began with the revelation of the corruption in the Tunisian government […] through the revelation of the WikiLeaks cables […] The most virulent attack on WikiLeaks was made on January 14, 2011” when “it was accused of leading the protesters in Tunisia astray by false claims against their incorruptible president [… this] violent attack on Assange was made by one Colonel Gaddafi.”

(In response to a question:) “At the end of the day you have the community standard that provides that ultimate judgment on the whistleblower” and “that is ultimately for a jury to decide”; “Governments make offers to” mediate “whistleblowers, telling its agents, ‘You can approach Congressmen with complete confidence if you’ve got anything to reveal’; that hasn’t been found to be effective. There is just not the trust that is necessary. The journalists by themselves are more trusted […] It is a principle of journalistic ethics that they do not betray a source.”

“Who judges the whistleblower? The answer is: the whistleblower begins” with a “moral imperative to make the disclosure” and “so long as there is a public interest defense, it would be a jury that would provide the ultimate decision.”

Question from the audience [me]: “Has the Swedish prosecution given reasons why they cannot ask Assange the questions over the phone or some other medium?”

Robertson: “No they have not. There is no doubt that Mr. Assange is willing to answer questions. He waited in Sweden for six weeks waiting to be interrogated […] He offered to talk to them from Britain by telephone or Skype or by any number of means and the Swedish prosecutor refused […] The Swedish prosecutor takes the view that when [and if] he returns to Sweden […] he should not get bail […] and [that] he should be tried in secret, because in Sweden these cases are tried in secret.” [Gasps from the audience.] “There will be a whole host of other issues, but it’s not particularly germane to the WikiLeaks issues themselves.”

Question from the audience: “You talked about corporations and governments needing to understand that confidentiality is really limited by the need of the public’s interest and that there’s a balance there. I was wondering [if you can] define what would be the public interest that would [override] legitimate confidentiality needs.”

Robertson: “This” type of publication is “power for the powerless to affect the way corporations behave […] It’s one way in which Internet technology can democratize corporate activity, make corporations accountable for human rights violations. I suppose there’s a failure — a black area — in international law saying corporations are not subject to international criminal law.” But this new Internet technology is a way “of making corporations liable for human rights abuses.” When “corporate insiders are offered by WikiLeaks-type organizations or even by the newspapers, which as I’ve explained are trying to set up WikiLeaks-style electronic letterboxes — where they’re offering that kind of anonymity as a guarantee — that may tip the balance and make [the insiders] more inclined to take the risk to expose” abuses.

Question from the audience: “So far we’ve been talking about the legality of WikiLeaks.” Can you say “how many of your resources you are using against the extradition & sexual assault issues versus [how many resources you are using to defend] the legality of WikiLeaks?”

Robertson: “These battles have been going on for a while. There’s nothing much, in fact, in the Swedish allegations; I won’t go into it because to do so would take some time. But it’s not been the Swedish allegations themselves that cause any worry; they may have to be faced down eventually, and I think Mr. Assange would deal with them willingly if the prospects for extradition to the United States” weren’t so likely. Sweden has a “regrettable record of supporting extradition to the United States” and it “has been exposed by the UN criminal court for doing that.” [Murmurs of surprise.] “The real problem is the grand jury proceedings which are of course cloaked in secrecy and have been going on a while, and the United States government hasn’t announced any position; it seems content to play a cat-and-mouse game; Alan Dershowitz and I are advising Mr. Assange on that.” Grand juries “can be open-ended”; they “haven’t been used in Europe”; they’re “unique to the United States. It may well be that the focus of concern will shift to Mr. Manning’s trial; that will come up shortly. It would be helpful, as I say, if the US Justice Department would say one way or another, if the United States government would say if they propose to bring a case against Mr. Assange.”

Loud applause.

Eric Schmitt of the New York Times

“The Assange I met was not the hi-tech terrorist as Biden described him nor the crusader as his lawyer described him. The Guardian had set up an awful Excel spreadsheet” for us to look through the documents in London. “Julian Assange was supposed to arrive and help us clarify the muck. There was this mystique about this guy.” The “Guardian was unclear about” where he was coming from [to London]; “it was Scandinavia.” Assange is “a striking figure: tall, lanky guy, about 6’2″ or 6’3″ with a shock of white hair.” He arrived “that night alert and disheveled in this kind of dingy coat, cargo pants, dirty white socks that sort of collapsed around his sneakers […] It was almost like Oz showing up to show you what’s going on behind the scenes. All he had with him was this huge backpack which he kind of sloughed off and from which were disgorged cables and” all sorts of computer equipment. And he had this “plastic box and he said, ‘In here are the crown jewels.'”

We needed to “figure out an arrangement for how we could get access for these documents back to New York.” It was “too long, too difficult” to go through the documents in the condition they were in. Once we achieved “access back to New York,” then “my colleagues using special technical means could essentially bundle these documents; we could give them search terms […] whether it was civilian causalities” or “relations with Pakistan.” And “over the next coming weeks as we did work out this arrangement with Assange and WikiLeaks […] we as a team at the New York Times in our own bunker […] were able to divide up the content of these documents and write up over the course of several weeks some five or six stories that ran in a package that day […] Assange had not placed restrictions on the material we used, he certainly didn’t” give us money or anything like that. He did ask for an “embargo”; he wanted it all to come out at the same time; “we had to settle on a common time and date.”

“With Assange, though, it was always a struggle figuring out who this guy was. He is a brilliant man to be sure, he’s very well-schooled in American history and American law,” and a “computer hacker, though he doesn’t like that term. He’s also incredibly paranoid, sees conspiracies everywhere, [and has] this kind of Peter Pan quality about him.” When “walking out with a Der Spiegel reporter, he started skipping ahead and humming this kind of tune” and then “continued the conversation.”

“The most difficult thing we had to deal with Assange” was what to do “about the names.” We at the New York Times “were very concerned about the safety of these individuals who had spoken to the Americans or the allied coalition […] it was very clear to us […] the Taliban would take a list, and they would remember and there would be a retaliation because that’s exactly what they had done [previously …] they had killed and intimidated [families …] so we took out names of individuals that we felt could be in danger […] we went to Assange and hoped” we could work together on redactions. Assange said, ‘That’s not what we’re going to do, we are an anti-secrecy organization. Sometimes there have to be casualties in this fight for transparency.'” That “wasn’t [our] position or that of” the Guardian or Der Spiegel. “We [at the New York Times] can’t be as certain as Geoffrey Robertson was now in claiming there was no harm, no injury [from these publications].”

“I participated in the workings of the Iraq War Logs which Assange had given us access to […] the diplomatic cables we did not get from Assange or WikiLeaks […] He was very angry with the New York Times […] throughout our collaboration our whatever you want to call it […] We consider WikiLeaks today a source, a very different source to be sure, but a source” [This position from the NYT puts all digital journalism, which is to say basically all journalism, at risk — DAL] “Julian Assange saw the four organizations in that room, that bunker in London, as journalistic collaborators. It depended on what day it was. On a certain day, Assange would say, ‘I’m a journalist today,’ and the second day, ‘I think I’m going to be a publisher today,’ and the third day, ‘I’m back to being an advocate’ […] Even he was conflicted about the role he played […] We [the New York Times] were not part of a crusade or the Musketeers or anything like that” [Why not? — DAL] He “was very angry we did not link to the WikiLeaks site.” Assange “was angry […] we did not stand shoulder-to-shoulder with him.”

“The impact of WikiLeaks has really set new standards, I think. This remains a gold mine not only for journalists but academic researchers. Any kind of story that comes up now, my editors say, ‘What’s in WikiLeaks about this story?’ If there’s a prominent new diplomat, ‘Go and search the WikiLeaks documents’; so, this is a rich trove of information […] It remains a very important source of information not only for understanding our foreign policy but to understand those we trust with our foreign policy […] Government has gone a long way to [ensure] this never [happens] again.” [Some government figure] “said it could take five more years to make sure our system is not vulnerable to another WikiLeaks-type attack […] Another effort of this kind is very unlikely. This was a perfect storm type of event […] The access that [Manning] had, the restrictions that were in place […] makes it very difficult to [redo] that.”

Assange “has contracted for a couple of books; those seem underway.” What takes the cake is that “a couple of weeks the RT Kremlin-sponsored news station” has agreed to host his television program. [RT bought the show; hosting is the wrong way to describe the licensing. –DAL]

“Bradley Manning is facing court martial now […] Obviously” Manning is “some disturbed young man.” But “it’s much less certain what’s going to happen with Julian Assange and what’s going to happen with WikiLeaks. This panel that’s in northern Virginia could very well issue some indictments, but it’s very unclear what path they may take.”

“We do have access at the New York Times of classified documents [as a general matter], but nothing like this; to get 90,000 electronic documents was overwhelming. There was nothing in those documents you could pull out and say, ‘Oh my God, that’s an incredible revelation’ — that’s not there. [There is however] a fine-textured, round-eye view of what’s going on with this war.” For example, “the number of IED attacks” or “the war is heating up again by 2007, and there’s no [help from the US government] despite the cries from the commanders.”

“The other thing [WikiLeaks] did was fill in gaps of stories we have written about [such as] the double-game Pakistan was playing with the United States […] While playing a very productive role helping the CIA round up Taliban, but at the very same time help the Taliban […] because Pakistan was taking a longer-term look […] because Pakistan wanted to make sure it had influence against its arch-rival India. So there’s this double-game that goes on to this day where Pakistan will cooperate in some areas but not in others […] Even if you discount half of these reports as biased by the Afghan intelligence service, it was still much more detailed than we ever had before […] Same thing with the Iraq documents.”

“WikiLeaks was severely chastened by the names released in the Afghan documents, so what did they do in these Iraq logs? They went the other way, using a computer program that took out almost every proper name […] if you get copies of the documents today, they’re virtually unusable. We had to redact, very carefully, a certain portion of the documents we put online. Robertson’s right in laying out the key stories that came out from these cables; these were finished diplomatic cables. What they’re saying in public is pretty much what they’re saying in private, but without so much detail.” [WTF. I list some of the cables indicative of lies here. — DAL]

“In my book with Thom Shanker, we talked a lot about the financing of terrorism.” The topic is “not as sexy as a SEAL team” blasting people. But the “funneling [of] a lot of money to terrorist groups” is important to understand; we talk about how individually these cables single out key allies in the Persian Gulf such as the United Arab Emirates and Kuwait […] This [Cablegate] was just a stunner to diplomats who have to deal with their counterparts every day […] You can imagine being a diplomat and having to face [the people you talk with] after this […] But it was also quite revealing in many ways […] as I think Robertson accurately pointed out, you had these cables talk about corruption […] I do believe this contributed to the Arab Spring. It wasn’t the sole cause, but it told people what they had all along suspected — but here are the nitty-gritty details. It did spark that [Arab Spring] outrage to a certain extent.”

“This is the latest issue of Rolling Stone with Michael Hastings interviewing Assange [Schmitt raises it in the air]. This is fascinating because Assange today, as he did then, criticizes the New York Times for this collusion with the United State government, [saying] that we’re in collusion with the CIA.” [In the article Assange does not mention the CIA in relation to the NYT, but rather says the NYT was “sucking up to the White House.” — DAL]. “But we believe our moral and ethical responsibility in dealing with very sensitive classified information” is to run it by the government. “We are going to write a story no matter what; that’s our going-in position with the government no matter what. [We ask the government] is there any reason” to treat this material differently. [The NYT says to the government:] “We’re going to give you a space to push back against this […] Are there any individuals we have missed that you think we should redact for their own personal safety […] Is there any sensitive information about intelligence [methods]” that we might jeopardize by publishing the story as-is. “We would have phone conversations telling [the government] ‘Here’s what’s going on with this classified information; we’re not giving you” prior restraint “here. Is there a legitimate national security interest in holding back material? This is responsible journalism. Respectable news organizations have always dealt with classified material like this.” [Questionable — DAL]

“This Administration didn’t come after us. In London we went through all these goofy rituals […] We couldn’t use our cell phones […] and we all kind of got into this.” We used a “secret code” to describe the information. “Package one was the Afghanistan documents; package two was Iraq; package three was the diplomatic cables. Because we didn’t know if the NSA was listening to our conversations.” [Contrast “goofy” with panelist statements below. — DAL]

“We have heated [internal] debates about sources: ‘Why is the New York Times doing this?’ Today I asked [a colleague], ‘Do you still have these concerns? It’s a year after these cables have come out. [My colleague said] ‘We still have these concerns, some day something’s going to happen to them [the informants]. But there’s been a chilling effect on our ability to acquire new contacts because WikiLeaks is out there. Everyone knows what it’s like to be WikiLeak’ed.” [I don’t understand how leak publications decrease the number of leaks. Perhaps Schmitt meant non-leak contacts are more afraid of the press now? — DAL]

“It’s a rare diplomatic meeting that doesn’t begin with a semi-serious joke: ‘What I’m about to say is not for WikiLeaks.'”

[People ask] “‘How could the American government be so incompetent to let this happen?’ It’s completely true we [as in the United States] classify too much. The State Department points their finger at the Defense Department, rightly so. The Pentagon came clean, embarrassingly so, about how little they had done to restrict this kind of thing. You had the ability to put a memory stick in a classified machine” and pretend to be copying Lady GaGa songs. It’s still an issue, “how little supervision there was over these classified machines.”

“The impact on journalists continues today.” Though “we have [already] gone through the big publicity burst of these documents, we continue to go back into the documents. The [Gitmo Files] did add more fidelity to our understanding of who’s being held in Guantanamo Bay. We dip back into WikiLeaks.”

“The State Department felt burned [by WikiLeaks] like no other agency did. [That’s] something that I think is really unfortunate for the transparency issue. After 9/11, the State Department lowered some of its walls” to help interagency communications “and that’s some of what Bradley Manning tapped into [and now] the walls have gone back up again.”

“Just some final thoughts on where this is going on the legal front. Lawyers are the guys trying to keep us out of jail.” One NYT lawyer, David McCraw, “offered some interesting observations here. David talked about how our Espionage Act […] has been written […] but so far it hasn’t been applied to publishers, it’s been applied to leakers. What McCraw later drilled into our editors and some of us were some of the things that makes it unlikely prosecutors will go after us. [That is] to redact sensitive information, giving the government the chance to have a space to push back, [discussing] what the public interest is in these stories […] What made it easier with the New York Times is that there were other, foreign publications that were going to go ahead with these publications, that wouldn’t have to answer to the US Government. The Obama Administration said let’s not go ahead with this at all, but if you have to do this at all, let’s do it in a responsible way. It really would have been pointless” to try to stop the global publishing.

“We didn’t want to appear to be collaborating with the Guardian in any way that [would have] made us” liable to UK laws. “We also wanted to maintain that distinction between journalist/source relationship with Julian Assange […] It was impossible to know just what he had done […] I asked Assange what he knew about Bradley Manning, and he would smile and say ‘We don’t know.'” But “these court proceeding seems to show otherwise.” And “could we at the New York Times be seen as aiding or abetting what Bradley Manning and WikiLeaks did? No one in the government has come after us. David [McCraw] also suggested to me that there are only three open-ended legal questions. The first is: ‘Should leakers have more protection?’ The Obama Administration has been very aggressive in going after leakers.” For example, a “former CIA operative named John Kiriakou has been gone after by the Justice Department for sharing information with reporters including one of my New York Times colleagues Scott Shane.” The mainstream news organizations have historically taken the position that it’s “illegal to leak” in exchange for the freedom for publishers to publish.” [Make an exchange in order to receive First Amendment protection? — DAL] “Courts have rarely recognized the right to retain and collect information. Are we” liable “if the government asked for the documents back? The Espionage Act could be read to allow such prosecution.”

“Would we sign on to an amicus brief to [defend] Julian Assange? Would we be reluctant at the New York Times to the lock arms with him?” [Questions posited as hypotheticals. His tone of voice and other remarks seemed to indicate the answers would be ‘No.’] “It’s always going to come back to the ‘Why we did this'” and “‘Why is it important to have to sources like this?’ We may never have WikiLeaks”-style “documents come this way to us again.”

“What did our most seasoned diplomats think of what we’re doing? Individuals who had nothing but casual contact with individuals might be captured or killed.” The questions “forced us to try to come to grips with what these different kinds of sources mean when we’re coming to this increasingly cyber-world. And finally I think it also underscores our obligation to verify this kind of material.” We’re back “where we started this conversation when I was sent to London. Are these documents forgeries or are they real? The ability to supply context is so important for journalists. And finally, ultimately, it’s to make sense of what’s complicated in a fast-paced world.”

Question from the audience [me]: “How much of the New York Times going to the government to give them a space to push back is really about maintaining access with the government to receive information, to receive authorized leaks and the like for domestic news and other information?”

Schmitt: We’re “not going to give the government the right of censorship, but [the right] to say, ‘You’re missing something here; you’re missing something about our operations and methods that you might be jeopardizing.’ They make their case; but, the decision to publish is up to us. Almost always we publish. There are small things we can do [such as] taking out a name that we think might not undercut the” overall story. “We don’t take things out because we think it will hurt our relationships with the government. It’s very rare that we get an authorized leak. It’s very rare to get the traditional brown envelope with documents. It’s more like a lawyer building a story by getting information from a variety of sources. The idea that [by giving the government a space to push back prior to publication] you’re somehow jeopardizing your relationship with the government to get freebie classified docs? It just doesn’t work that way.” [I’m not sold — DAL]

Question from the audience: “Do you think Assange has an ideology beyond transparency?”

Schmitt: “I don’t know. He clearly has an anti-war philosophy; that came through quite clear. There were some estimates coming from the Guardian of higher numbers … clearly this is something we went through very closely.” [This might have been a reference to Special Task Force 373 numbers, discrepancies noted by Jason Leopold — DAL]

Question from the audience: “You talked about bloggers; I wanted to see if you had any comment about Glenn Greenwald …”

Schmitt: “That’s probably a better question to ask to my colleagues such as Scott Shane.” Greenwald’s “voice is valuable. Like most bloggers, he has a point of view; you have to be careful with that.”

Question from the audience: “Had those documents not been acquired from WikiLeaks […] would have reported on it […] differently?” [I didn’t quite hear the question — DAL]

Schmitt: “We got the final tranche of cables from the Guardian; that’s public knowledge. We had a falling out with WikiLeaks. He felt we weren’t being fair to him. He was particularly upset about a profile we wrote about Bradley Manning and a profile we wrote about him. I don’t think we would have written it any differently. The source is giving you documents; then you have to look at the documents themselves. Julian Assange needed these news organizations and their technical skills as partnership, collaboration, whatever — he thought it was more of a journalistic collaboration. He just felt he didn’t have the technical skills” to analyze them journalistically. “He was savvy enough to know that and pick the new organizations that he did to have that impact. WikiLeaks is an unusual organization. It was, before it started imploding. Its main branch was in Germany; that was where a lot of its funding and volunteers came from. But it had branches in Scandanavia and this branch in Iceland. He knew he had a more sensitive liberal audience in Europe. He had El Pais in Spain and Le Monde in Paris for the diplomatic cables. Is his organization starting to fracture from internal fighting? People took the documents with them, virtually, and they started popping up. He started losing control of his organization.”

Concluded by moderator due to time.

Panel

Lucy Dalglish [Reporters Committee for Freedom of the Press, Executive Director], Don DeGabrielle [private international governmental investigations attorney, former U.S. Attorney, and former FBI Special Agent], David Adler [federal criminal defense attorney and former CIA officer] and Tom Forestier [Moderator; law firm managing shareholder].

Dalglish: “WikiLeaks is an inevitable thing; it’s the collision of technology and national security; if WikiLeaks didn’t do it, someone else would have invented it.”

Dalglish: “What makes WikiLeaks different than the Pentagon Papers is the speed and volume of the information. I understand why this makes various people in the government very anxious and very angry. I think they’re responding not so much to WikiLeaks and what it did, but what will happen next time.” These documents “were not the ‘crown jewels’ […] What happened in the WikiLeaks case was good journalism.”

Dalglish: “The question, wherever I go, is, ‘Is Julian Assange a journalist?’ Under the Espionage Act, that really doesn’t matter. Whom it really matters to are the journalists who have been out there year after year because they want the public to understand the process of what they are doing, the fairness. They really, really care. Under the law it doesn’t really make that much difference, except the US government has shown the more you are acting like a journalist the more they leave you alone.”

Dalglish: “The first group of documents was really dumped out there. Julian Assange started as identifying himself as an advocate, but more and more as a journalist; I think that was something his lawyers advised. And as time went on [WikiLeaks] started paying more and more attention to people on the ground. That’s just what I’m surmising they did.”

Dalglish: Assange “putting himself in the position of a journalist puts him in a better position if he were to be charged in the United States.”

Dalglish: “I was at a meeting at the Wye River Plantation, which is owned by the Aspen Institute. It had been a long time since there had been a meeting between intelligence chiefs from the CIA, the Justice Department, the military” and more. “I was flattered to be invited. The ground rules were, we could report on what was said, but we could not report who said. It became very clear — because they point-blank said it — that they do not believe there is even the slightest possibility of there being a whistleblower in the national security arena. There are whistleblowers in government, but not in national security. If you leak national security info, you are not a whistleblower — you are a felon. Period. That is the attitude this Administration takes. At a meeting this was verified by the president himself; he said to us” there are whistleblowers “but that doesn’t apply in the national security arena.”

Dalglish: James Risen has been “fighting a subpoena for many, many years.” I was told at that [Wye River Plantation] meeting that “by the way, this Risen subpoena is the last one you guys are going to see. We don’t need you anymore; we already know who you’re talking to.” And then Jane Mayer’s “article came out about Thomas Drake, about how the government is capable of tracking everything you do. Reporters, if you have a source to protect, stay off cell phones, stay off email; do what Bob Woodward did: use flowerpots, balconies, and parking garages. Look how long he was able to protect those sources using tried-and-true methods.”

DeGabrielle made a joke that Robertson’s Skype call interruption might have been shut down by the US Government.

DeGabrielle: “We believe firmly […] that indictments have a lot of power — they can ruin lives, families […] don’t just do it because you can.”

DeGabrielle: Quick point about Robertson’s remark on rendition and extradition. “They’re not the same thing. Rendition happens like with our neighbor to the south, Mexico. They’ll show up in the middle of the night with someone we in the United States want. They’ll meet us on a bridge and” hand them over “and we’ll say thank you and adios. Renditions, they’re not” chock-full “of due process.”

DeGabrielle: “If the United States wants to prosecute Julian Assange, I rather suspect there will be an extradition hearing, and it will get done.”

Adler joked that with a criminal defense attorney background and a TV photographer background, he [Adler himself] must be very conflicted about WikiLeaks.

Adler: “I can tell you with the contact I maintain with my friends who are intelligence officers that people have been affected by this. Careers have been destroyed in the foreign ministries. You can imagine what your boss would do if he found out what you really think about him. Lives have been devastated by this. I’m not aware of anyone having been killed, but to say that no one has been hurt — I don’t agree with that. It comes down to your responsibility to your fellow human being. I understand the concept of leaking, and frankly, I’m in favor of it; the government makes a lot of mistakes […] but people are at the heart of the” issue. “My problem with Mr. Assange is, I think Mr. Assange wants the story to be about Mr. Assange. For whatever reason Assange chose not to” redact sufficiently “but being anti-war and still being willing to risk their safety [i.e. safety of informants] — it seems to be a contradiction to me. Even Mr. Robertson said” about Sierra Leone “he was very concerned about sources coming forward with information and being killed.” [I didn’t hear clearly the part where Robertsont brought up Sierra Leone; that’s why it’s not included above. — DAL]

Adler: “There are tremendous parallels between being an intelligence officer and being a journalist. Mr. Assange’s method does more to endanger journalists. I think you go to the government and say, ‘We’re going to do this, but what do you have to say?’ It is the moral thing to do, but it also has a practical effect: [it makes it] less likely that the government is going to come after you. So just to willy-nilly throw yourself out there with these documents, I think, was a very unfortunate difference.”

Adler: “There is some value” in the WikiLeaks documents. “And I think there’s some deterrence value in having government employees concerned someone’s going to leak their misdeeds. Mr. Schmitt mentioned this CIA officer Kiriakou who was indicted just this past week. The similarity between his case and Mr. Assange’s case is he also wanted to be the center of the story.” Kiriakou “was clearly enjoying the publicity. By the same token, he could have done it the way that got the information out” without getting his name all in the press. “As a CIA officer we were very wary of sources who wanted to be the story. Number one, the information may be suspect. But number two, you may end up being clients of Don and myself. Look for the good information, publicize it when you think it’s appropriate, but do it in the appropriate manner. I don’t think disclosing the names in many of the instances is” the right way to do it.

Forestier: “One of the comments that Mr. Robertson made that I found to be very intriguing is whether or not the government needs to do a better job of keeping its secrets secret.”

DeGabrielle: There was the “Vanessa Leggett matter where a subpoena ‘was issued to someone who called herself a journalist. She was writing a book; she recorded a conversation in secret.” [DeGabrielle said more about this Leggett matter, but I couldn’t transcribe it quickly enough since I wasn’t familiar with the case. — DAL]

DeGabrielle: “Don’t think if you’re using a cell phone that the government doesn’t know what is going on.”

DeGabrielle: “I agree it’s a responsibility of the government to maintain the confidentiality it is swearing people into” [I missed the rest of this –DAL]

Forestier: “Lucy, can you share with us about the Valerie Plame affair?”

Dalglish: “Okay, that’s like my least favorite case of all time. You know, the parallels, I can’t draw too many parallels to that case because the Plame case was a situation where there was a lot of debate over whether yellow cake uranium, I think, was being gathered by Iranians. A columnist by the name of Robert Novak wrote a column” in which “he identified, in a kind of offhand way, that the former ambassador they sent to Niger was married to a CIA employee named Valerie Plame. The mention was almost gratuitous. In that particular case, I would distinguish them by saying the WikiLeaks case is a matter of the national intelligence agencies sitting down and being very, very concerned and having a kind of meltdown over the damage that could be done with the government. With the Plame case there is far more politics […] there was Scooter Libby, Karl Rove […] and multiple reporters involved in all of it; there were political columnists involved in all of it […] There just weren’t all that many similarities. Did the release of Valerie Plame’s name do incredible damage to her career? Yeah, it did. To this day I don’t understand why publishing her name was necessary.”

Adler: “From my years in the” intelligence community / CIA … When “someone in the family breaches that trust,” the family is “beyond furious. It’s like your wife or husband cheating on you; you’re that angry. With someone who’s made a member of ‘the Brotherhood,’ let’s say, would turn it around to get their name out there and risk people out there […] I think Obama has prosecuted six of these cases […] I don’t think it’s a decision made in the White House, I think it’s people in the national security agencies saying shut this down, it’s getting out of hand.” [Dalglish nodding her head.] “Manning and Drake will be the subject of CIA training videos. Although I agree the Plame thing was politically motivated because Joe Wilson, the ambassador who was sent over there, was a Clinton appointee.”

Dalglish: “Reporters were calling me and saying, ‘Doesn’t this Plame affair have a chilling effect on reporters?’ And I’d say, ‘Don’t you think that’s the point? Yeah.'”

Dalglish: “Mostly” protection for sources “involves staying off the phones, acting more like a CIA operative.” Your airline tickets and more are being tracked. “They are trying to track people who are leakers.” The government “will kind of ‘go back’ and look for the connections with the reporters who did the stories. It is kind of a lesson from the Plame-Cooper-Liddy-Rove case, and this is, when you’re communicating on your employer-owned communication devices, your employer is going to take the position that that information and that product belongs to them. And under the law that is probably true. So as Matt Cooper found out, after he fought the subpoena” TIME Magazine lost, and someone at TIME “thought he had the duty to turn it over. So TIME Magazine turned it over. So that’s another thing you guys have to pay very careful attention to. So Eric I’m sure knows all of this, and the NYT and David McCraw know all of this, and they’ve probably told everybody these things. Basically, stay off technology if you have somebody you seriously need to protect, particularly if they are in the national security world.”

DeGabrielle: “In the U.S. Attorney’s office, email is referred to as ‘evidence mail.’ We hear about horror stories of people who’ve said certain things in email, and they still don’t think about it, the confidentiality of the employees at a company, or even among the government. Electronic information is just cascading […] I think we’re going to have to redo some of the laws. This generation thinks there’s instant access to anything, so what’s the harm in reading something WikiLeaks has divulged? I would like to see” the matter raised: “does the public really need to know? Or are these salacious details that people would just like to hear about? Frankly, the people who are the decision-makers now are a bunch of dinosaurs who didn’t grow up with this, so they’re basing information on outdated information about what’s out there […] Everything is going to be available to everybody. I think David pointed out, and I think Lucy has said it as well, that the government probably classifies too much, and you get” agencies “that protect their turf. In a perfect world we’d have a super classification agency, one kind of ‘pinnacle’ that’d understand what it takes to get something classified. However, that’s impractical. No single group […] is going to be able to make that call.” The government “needs to think more in a sober fashion before they put that stamp on their confidential or their top secret or whatever it happens to be and think about it before the stamp goes down and why.”

Adler: “I gave a talk a while back to some civil lawyers titled ‘Delete Doesn’t.’ So not only should you not communicate” via technology, “but you shouldn’t think deleting” is sufficient. “Forensic people” who work for the intelligence agencies “are spectacular.”

Adler: “A quick story that illustrates how bizarre the government is with classifying things. When I was with the [CIA] agency, you have to put everything in your desk at night, [your] safe, lock it up. I had this friend who just had a blank piece of paper there and was stamping SECRET all over it [for fun]. When I got back the next day, there was the equivalent of a CIA speeding ticket on my desk! And the paper was blank!”

Forestier: “About post-9/11 integration of intelligence agencies to help one another … Do you want to comment on that, anyone?”

Adler: “The government bureaucracy does not — They’re not very good at the appropriate response to the problem. It’s all or nothing. After WikiLeaks they don’t want anyone to share. They swing back and forth between these extremes, and it takes a long time to work out the mechanics. I’m not surprised this Assange thing — and let’s be honest, there’s still rivalry between the FBI and the CIA, between the CIA and the State Department. ‘Those weanies over there don’t know what they’re doing, so we need not send something over there for fear it’ll make it over there to Assange.'”

Dalglish: “I can tell you that just being in Washington and talking to various people that the rage over this particular [WikiLeaks] incident, the folks I’ve spoken to, the rage seems to be mostly focused on the Pentagon. So honest to God, as an outsider who doesn’t know much about this […] it blows my mind that a twenty-two-year-old Army private with known psychological issues has access to information that two and a half million people.”

Adler: “I think that two and a half million figure is inaccurate. It’s more like 300,000 to 400,000.”

Dalglish: These groups “trying to co-ordinate publishing –” [Something I didn’t catch — DAL] “In most other parts of the world, reporters have a right to protect confidential sources, but they are subject to censorship” including in the UK. “But in the United States, they’re not going to block you from publishing unless it’s something extreme or imminent, but they do have the right under the law to come after your sources. So I would think that the publishing partners in the UK must have been apoplectic when the folks at the New York Times went to the government and said, ‘We’re about to publish it, what do you think?’ The Guardian must have been thinking, ‘Oh my God, the White House might call Downing Street” and tell them.

Schmitt (from the audience): “It did come up. The way it worked was, the lawyers got together and talked about it, and as long as the New York Times got together and talked about it, and as long as the New York Times published before the Guardian or before Der Spiegel, even if it was just a minute or two more, they were released from that obligation. By the time we got to that point, the Guardian was less concerned about the impact because the UK had realized this stuff is going to come out — it’s futile to block it.”

Adler: “That middle-ground […] It can be revealed to a journalist, but it can be done in a way that makes it difficult for Don’s old colleauges to come after you. Maybe I’ll make my fortune teaching spy tradecraft to journalists […] It may need to be journalist-source-lawyer more than it has been in the past; lawyers can’t go over the line and tell people how to break the law.” But “some of you who are at smaller outlets need to, maybe, contact Lucy’s organization and say, ‘Hey there’s this situation I’m facing; I don’t want to step on a landmine.'”

Dalglish: “There are several bills that are in Congress trying to adapt the Espionage Act. There are some significant efforts to rewrite it. I don’t think it will happen in the next few months because Congress is not doing anything at the moment.” But “they are spending a considerable amount of time on the Hill with media trying to make sure people in the media understand the government’s point of view on this particular issue.”

Conclusion.

I asked Dalglish after the panel what she thought of the argument that WikiLeaks is accountable since it depends on donations from the public. She thought the notion ridiculous and said legal accountability and financial accountability are distinct. After all, “people will buy anything.”

I asked Adler about the nascent US prosecution against Assange after the panel and he said to me one of the major issues surrounding the Assange case is whether “we [the United States] can drag his ass over here.” Obviously I don’t support that.

Houston Law and Media Seminar on WikiLeaks (January) #WLTex by Douglas Lucas is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License. Based on a work at www.douglaslucas.com. Seeking permissions beyond the scope of this license? Email me: dal@douglaslucas.com.

Twitter:

Twitter:

Join the conversation